“I’m Louise,” she said, extending a hand, “from the Sandhills of Nebraska!”

She drew it out for emphasis: “Saaandhiiills.” She grinned as I reached for her hand as though smiling at her own joke. She was lanky, animated. Her curly hair followed the quick, birdlike movements of her head like a visual echo. We stood beside a dining table on the second Wednesday of our first semester. She wore a long cotton dress—unusual among the typically jean-clad students. I recognized her from Latin class.

“I’m Dan,” I said, “from Boston.”

I was not actually from Boston. I was from Lexington, Massachusetts, a suburb. But here in the Midwest, I didn’t expect anyone to know where Lexington was—if anything, they’d think I was from Kentucky. So I said “Boston.” I’d said Boston a lot those first two weeks as I met fellow students. In a small liberal arts college with a national draw, they could be from anywhere.

But they were not likely from the Saaandhiiills of Nebraska. That was a vast, remote, arid, steeply rolling grassland. Its population per square mile was not much greater than that of the moon. I knew this: My roommate was from Western Iowa and had spent the past summer on a sprawling Sandhills ranch.

“Boston!” said Louise 1. She gave a little jump of surprise, then sat down. She pulled out the chair next to her and patted the seat. “Well, you just sit down right here, Boston, and talk to me!” I was instantly charmed.

Louise was an open book, and the pages turned quickly. As we started our salads, she told me she was a cattleman’s daughter from a remote ranch “waaaaaay out in the country.” She’d gone to a tiny rural school, then a slightly less tiny small-town high school. Her entire graduating class “could fit around this dining table right here,” she said. Then she’d enrolled in the nearest state college. During her sophomore year, her work had caught the eye of a young English professor there, a Harvard alum.

“Harvard!” Louise said, sticking her fork in the tater tot casserole. Her inflection suggested an Ivy Leaguer turning up at Podunk State was as likely as that college winning the Super Bowl.

“In Boston !” she added.

(“Cambridge, actually,” I thought, “but what does the Charles River matter?”)

Louise continued: “Well, he said I should get the heck out of there if I wanted a good education! He told me I should come here. So here I am!” She spread her arms wide, taking in the cavernous, brick-and-limestone dining hall’s cathedral ceiling and three-story-tall stained glass windows.

I was doubly charmed. Her transparency and her wide-eyed, small-town, imagine-little-old-me-ending-up-here narrative had a Dorothy in Oz quality to it. With her long skirt and spare build, she resembled more the Wicked Witch of the West than Judy Garland. But her animated, curl-ringed face was as open as the Midwestern sky. She had none of the reserve of the East Coast students; none of the hip affectations of the West Coasters. And she out-friendlied even her fellow central staters by a country mile.

“So what’s it like growing up in Boston?” She cocked her head slightly and looked at me intently.

I smiled. Clearly, that English prof had made quite an impression. I was a surrogate, I realized. I felt both amused and undeservedly venerated. I didn’t want to disillusion her, and her unguarded openness deserved honesty.

“Well, I’m actually not from Boston,” I confessed, taking a bite of the Jell-O.

A brief, “then why would you lie?” cloud flitted across her face.

“I’m from a suburb 15 miles away.”

Her face lit up again. “Well, heck, that’s close enough! What’s its name?”

“Lexington,” I said, expecting a blank look.

She gave a little gasp. “LEXINGTON! Where the Revolutionary War—”

“—Yes, yes,” I rolled my eyes. “‘The shot heard round the world’ and all that. They crammed it down our throats every year in history class. And there are so many tourists there in the summer you can’t park downtown.”

“Wow! And have you been to Con-cord?” She pronounced it like the synonym for “agreement.”

“Well, we call it CONK-erd,” I grinned. “Yeah, it’s just 7 miles away. I bought my bicycle there.”

“Golly!” she said. “I have a class now, but we have to talk! See you in Latin!”

And off she went in a swirl of cotton.

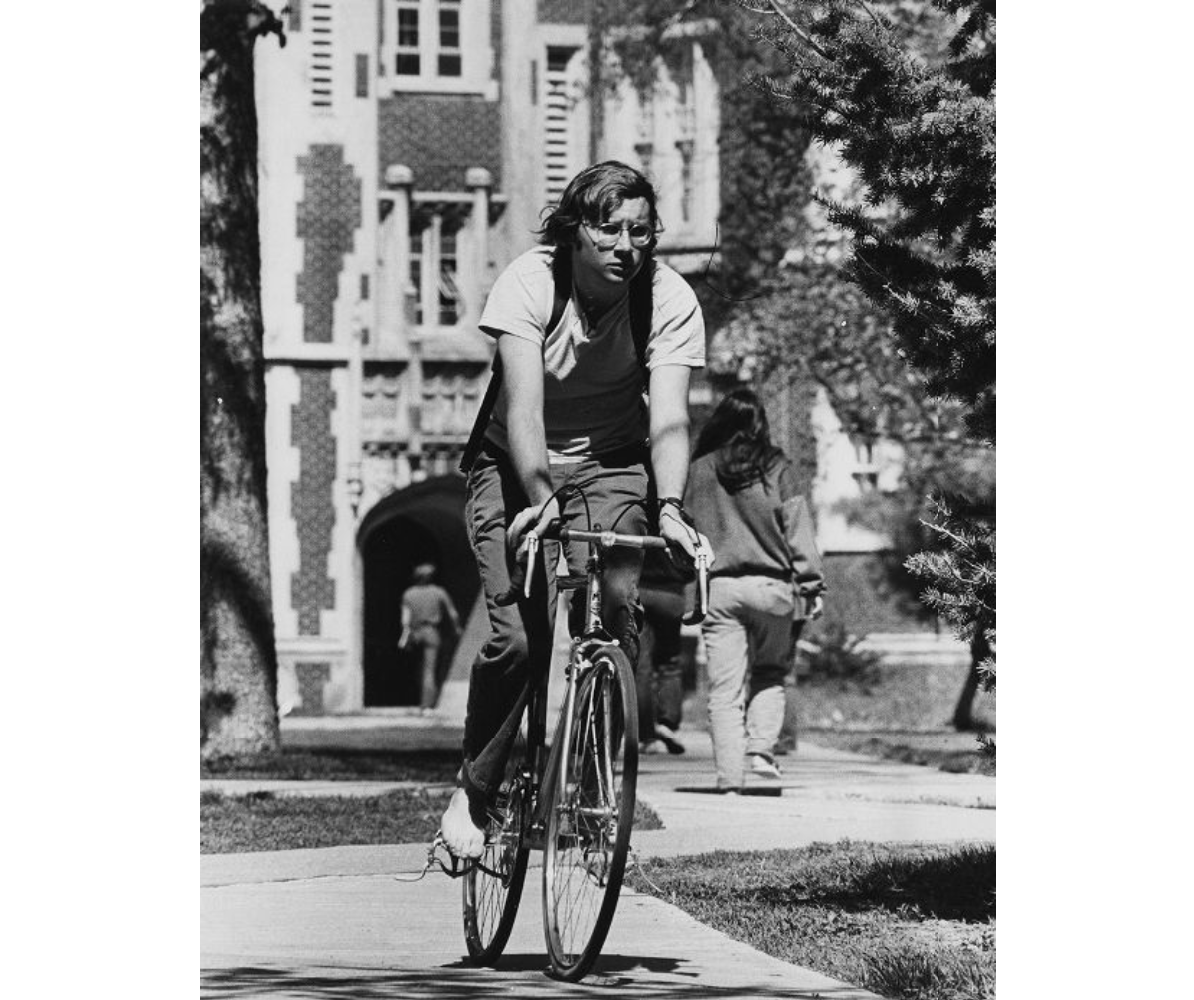

Photo of a student riding a bicycle on campus, 1970s. Courtesy of Grinnell College Archives.

Next Latin class was Friday. I arrived early, anxiously opening my textbook and rescanning declensions. Latin was tough, and the prof took it fast. Two weeks into class, I felt I was already a month behind.

Louise breezed in just before the bell, scanned the room, and gave me a big smile.

“Haaay, Boston!” she said and plunked herself in the seat next to me.

She hadn’t been kidding about wanting to talk. As we walked out of class, she resumed interviewing me about the fairy-tale land of Redcoats, Minutemen, and the Ivy League. She paused where the North Campus sidewalk diverged from the South Campus path.

“You know,” she said suddenly, hugging her Latin text, looking straight at me, twisting her body back and forth, fanning her skirt. “Nobody here goes on dates. Heck, they just mingle! You know? Throw frisbees? Play stereos out the window?”

I nodded.

“Let’s go on a date !” said Louise. “There’s a party at Cowles Hall tonight. Pick me up in Dibble Lounge, 7 o’clock. And dress nice, like a real date! Not like everyone here in torn jeans. It’ll be fun!”

It was less an invitation than an assignment—one I found impossible to refuse. She needed a date: There I was. From Boston, to boot.

“Sure. I guess!” “Great!” she replied. She impulsively grabbed my shoulder for a second, laughed, pirouetted, and strode off down the path.

I walked toward my room in Cleveland Hall, shaking my head and chuckling. After my astonishment wore off, I thought, " Of course. She thinks I’m from the formal and cultured East where young people meet in drawing rooms and promenade to wherever people promenade to, I suppose. "

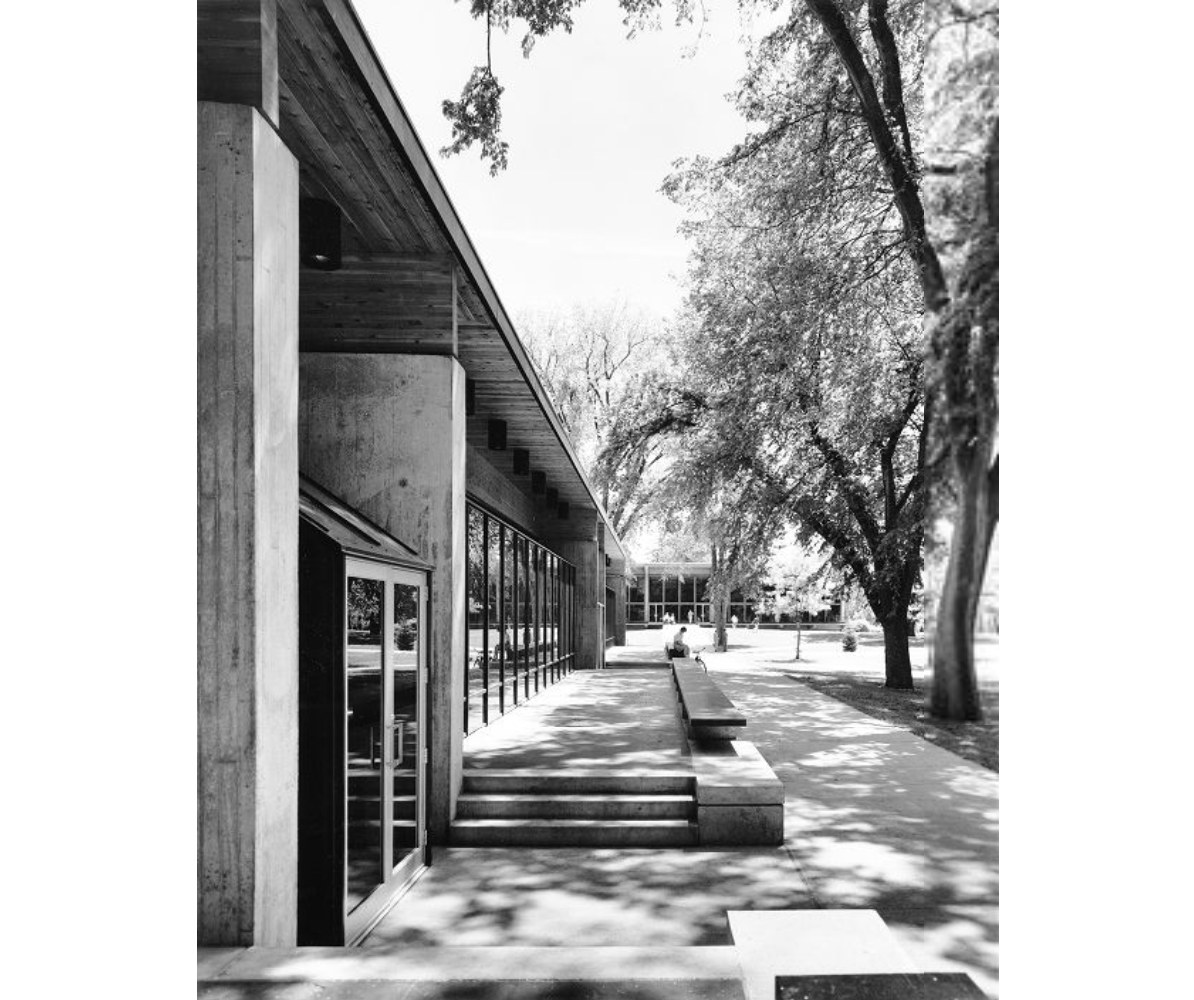

View down west side of Forum towards Burling library, 1970s. Courtesy of Grinnell College Archives.

Actually, I’d never been on a date. Well, just one, with Leslie Morgenstern, to the James Bond flick Live and Let Die in 10th grade. We’d walked to the theatre in silence, neither of us knowing what to say. The walk back was the same.

So I avoided poor Leslie 2 after that. She was nice—and cute—but as gawky as I. We were too well matched, I decided. Someone needed to start the conversation, and neither of us was up to it. I wasn’t going to put us through another evening of Live-and-Let-Romance-Die.

I did have a high school girlfriend eventually. I got to know her as a fellow member of a big church youth group. None of us dated, but some gradually coupled into steady companions. We wore jeans and played frisbee outside during lunch period at school. I had imagined my college social life would be similar.

Thus I’d not come to campus prepared for formals. My clothes, like those of my classmates, were extremely casual. I’d crammed a bunch of t-shirts, cutoffs, slightly-too-short khakis, and such into my great-uncle’s steamer trunk. These had traveled under high compression in the back of my parents’ car. When I’d unlatched the trunk in my dorm room, my wardrobe had exploded into a gradually expanding wrinkled mass. With some effort, I’d stuffed it into my little college-issue dresser.

Going through the disorganized drawers, I found a pair of socks that were not white crews. My mother had packed my one sport coat over my objections. “This isn’t the ’50s,” I’d told her, but she said I might need it for something. There was also a scrunched-up, clip-on bow tie I’d brought along (I never had learned to knot neckwear). I’d decided to swap my usual sneakers for the scuffed Clarks Wallabees under my bunk.

As I assembled my ensemble, I told my roommate, Devin 3 , that I had a date with a gal—a junior, no less, a transfer student from Western Nebraska. Like the rest of the student body, Devin didn’t date per se, and generally wore thrift-store attire. But having been to the Sandhills, he respected the ritual. I looked at myself in the mirror and gave him a dubious, questioning gaze.

“You look fine,” Devin said. “Have fun.”

I walked across campus in the gathering dusk. A smattering of students crisscrossed the quadrangles, heading from the library to their dorm rooms or from the dining hall to the early movie. Serious partiers weren’t out yet. But apparently Louise didn’t want to waste any of the evening.

“Hey—what’s that on your neck?” asked a passing male student in mock alarm, pointing to my bow tie. I grinned and shrugged as if I didn’t know either.

I arrived at Dibble Lounge at the appointed hour.

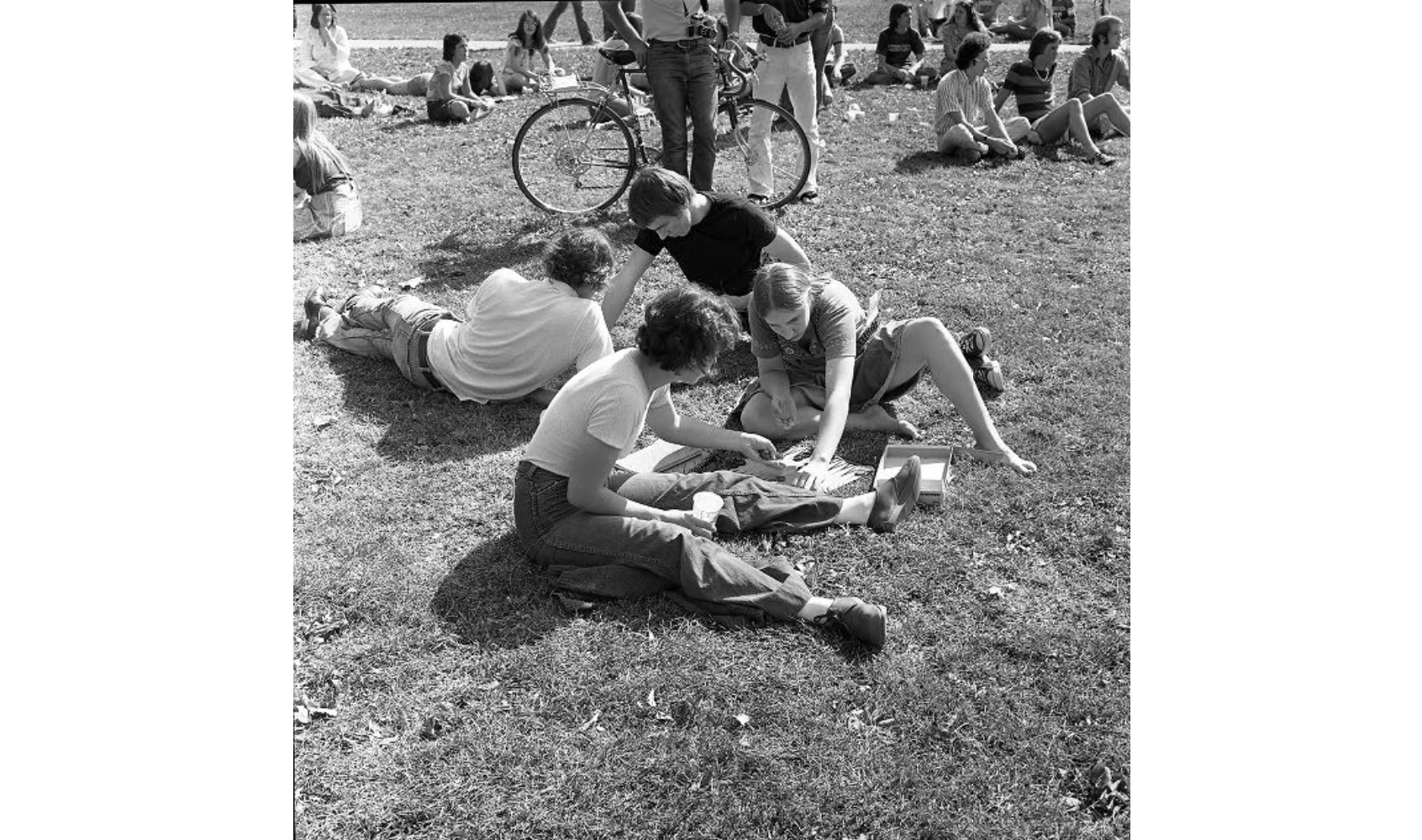

Grinnell College students in the 1970s. Courtesy of Grinnell College Archives.

“Haaay, Boston!” said Louise, jumping up from a chair. She swept across the floor and linked her arm to mine. Loungers looked up, bemused that Louise and Some Guy were Going on a Date. Louise glanced around, giggled. “Bye, Dormies!” she said. Apparently, my attire had passed muster. We walked out into the cool blue North Campus evening.

I already felt fond of Louise. Who wouldn’t? In spite of my shy, awkward self, I knew we’d not lack for conversation. She was the anti-Leslie—so vivacious, it seemed impossible to be self-conscious around her. This would indeed be fun, just as she had said.

We arrived at the party in the second-floor lounge of Cowles, the dorm next door. Louise grabbed a plastic cup and topped it off from a keg; I poured myself some punch. We joined about half the party in climbing out a lounge window that opened on to the big, flat roof of the dining hall below. Louise and I sat on the low parapet that rimmed the roof.

“Here we are from all over the country,” she mused as we overlooked the gathering in the dimming twilight. I was thinking the same. Until a couple weeks ago, I’d not been west of Pittsburgh, where my cousins lived.

In response to Louise’s questions, I told her I rarely went to Boston. That my high school class—not the school, just the class—numbered more than 700. Yes, I had bicycled past the Lexington Battle Green almost daily on the way to school. No, I’d not toured the adjacent Buckman Tavern, where the Minutemen had regrouped after the brief skirmish of April 19, 1776. That I’d played trombone in a high school band large enough to hide that I couldn’t march worth a damn. That for fun, I’d piled my friends into my father’s pickup and we’d gone to American Foreign Service movies.

I suddenly realized I was as provincial as Louise—more so, as I had so many opportunities not to be.

Louise told me it took “forever” to get from her ranch to high school over miles of two-track lanes and more miles of gravel roads. Driving her family’s “school car,” she’d pick up other rancher kids on the way. In bad weather, she could be stuck in town or on the ranch for days. I had thought country kids lacked extracurriculars. Louise set me straight: At a high school where students numbered a few dozen on a good year, everyone participated in everything so that the school could put on a play, field a team, assemble a choir. She often didn’t get home until after dinner.

She spoke of home as both far away and long ago. I was amazed by her perspective after only a couple weeks on campus.

I asked about dating.

“Oh, yeah. Everybody dated,” she said. Her boyfriend was a ranch hand, predictably. When she’d gone “away” to college at Podunk State, he’d visited her Saturday nights. He drove a souped-up, dark blue ’69 Chevelle he’d named Midnight Magic.

“Can you believe it?” Louise laughed as though she suddenly could barely conceive of it herself. “Midnight Magic!” He’d lettered the name on the car’s back window.

“Yeah, he’s a big husky fella,” she said. During high school, he’d taken her to school dances. He’d stand on the edge of the gym in straight-legged jeans and western shirts and cowboy boots and talk with his buddies while Louise caught up with her girlfriends.

“The guys all had CBs,” she said, referring to the 1970s fad of installing citizens band radios in cars. CB jargon quickly became a badge of cultural identity with young bucks, particularly in the rural Midwest.

“Everything was ‘Ten-four, good buddy;’ ‘Catch you on the bounce, good b uddy,’” Louise said. She laughed again, as though she all at once found it absurd.

“All the guys drove a ranch pickup with a gun rack in the back window,” she continued. “Except for Midnight Magic, of course. After the dance, you’d find a road to an abandoned ranch or a turn-off down a draw and park and make out. At the next dance we girls would gossip: ‘Are Billy and Martha doing it?’ ‘They have to be.’ ‘She wouldn’t let him.’ ‘Oh, yes she would!’” Louise giggled. “That’s pretty much what we talked about.”

I pictured trysts on the broad bench seats in pickup cabs, dash lights glowing, moonlight streaming through misted-over windshields. Couples taking care not to knock the loaded shotgun off the rack.

“That was my life,” she said with a sip of her beer. “I could see the next 50 years from there. Gettin’ married. Ranchin’. Kids.” And then she’d encountered Professor Harvard. English literature. Now Latin. Unlike me, she was breezing through the assignments.

She stared into the milling crowd. Her eyes lost focus. Louise seemed to realize, just then, that her Nebraska life was over. Or so it seemed to me.

She would let her husky boyfriend (“Fiancé,” she corrected me, “for nine months!”) down as gently as she could, no doubt. In his heart, I imagined, she would forever be his first love. The one who went to “colleege,” as it is often pronounced in the rural Midwest, and never returned. “Wow,” I thought. I was a third-generation college student—grandson of an English professor, son of a Ph.D. physicist and a conservatory-trained classical pianist. I’d been raised to go to college, then to graduate school, and on to a profession. Which profession was unknown, but I had been told it would arrive, certain as the dawn, in due time.

Still, college was proving all I could handle, socially and academically. A bit more, actually. Louise suddenly seemed vastly more mature and worldly than I: She had already lived an entire life, had chosen to leave it, and was starting another. I felt a surge of admiration for her. In fact, I was a bit awestruck. She and I had changed places in the who-was-impressed-by-whom department. At least in my mind.

It occurred to me I really wasn’t her date—and certainly not her prospective boyfriend. Consciously or not, she had chosen me to be with as she bade goodbye to one life and embraced another. It was a ceremony worth dressing up for and not one you’d want to go to alone. I rested my hand on hers. She clasped it—reflexively or deliberately, I couldn’t tell.

A fellow partier stumbled and landed in front of us. He squinted up at us as we sat side by side on the parapet. I recognized him. He was the exceptionally shabbily dressed senior in my Historiography class who kept bringing up Karl Marx out of context. His eyes were spinning.

“Is tha your girlfrien?” he asked somewhat indistinctly. Louise came out of her trance and giggled.

“Actually, we’ve just met,” I said.

“Mine just left with another guy,” he said. “I don’t care. Don’t care what she does. I’m an existentialist,” he explained. “Nothing is real, remember that.”

Louise nodded solemnly for the existentialist’s benefit but barely concealed a laugh. The existentialist struggled to his feet. He looked around distractedly for his beer cup. It had departed his hand and spilled on its way down. He failed to find it and wandered off. Louise and I climbed back through the window and left the party soon after that. We promenaded around campus in the dim yellow glow of the sidewalk lamps—past the humanities building, past the post office, past the bookstore, past the ivy-covered chapel. The leaves on the towering cottonwoods were beginning to turn and fall. We passed a row of three-story dormitories, windows ablaze. They looked like a convoy of ocean liners about to set sail.

We marveled at how insular the campus was—four blocks of quadrangles walled from the town and surrounding cornfields by academic-gothic residence halls. We passed an arched opening between two dorms, each with a crenelated tower. Looking through the arch, we could see the horizon.

“Is Harvard like this?” Louise asked.

“No. Well, kind of,” I said. “It’s way bigger and way older. And the sidewalks are brick. But it has a bit of the same set-apart feel.” She nodded.

Eventually we ended up outside Dibble Hall, Louise’s dorm. I wasn’t sure how this should end.

Louise knew: “Give me a hug, Boston!” she said. We embraced.

“God, you’re skinny,” she laughed.

At 5 foot 10 inches and 145 pounds, I should have known that. I’m skinny , I thought. How about that?

We said goodbye. I walked back to Cleveland Hall in a daze.

In my room, I took off my bow tie, my jacket, my Wallabees. I stretched out on my bunk and gazed at the ceiling, hands laced behind my head. Soon Devin returned from the late movie.

“How was it?” he asked.

“You know, it was ab-so-lute-ly wonderful,” I said quietly.

“I wasn’t who she thought I was though,” I added.

Then again, I thought to myself, she’s not who she thought she was either.

1 “Louise”, “Devin” and “Leslie” are pseudonyms.

2 ibid

3 ibid