The following is a criticism of three postcards from early 20th century Oklahoma that depict images of Native Americans. I recognize that my position as a white woman writing this piece is a privileged one, as people who have looked like me have historically been destructive to the livelihoods of people of color, especially those who are Natives of the land that is now known as the United States. The goal of my words is not to amplify my voice over others; it is instead to criticize specific postcards that stereotype Native Americans, explicitly the Pawnee as well as tribes that are left unlabeled on the cards.

To read more about the Pawnee Nation, visit their site: https://pawneenation.org/pawnee-history

The Oklahoma Department of Libraries’ digital archive is home to a collection of a twentieth-century tourist staple: postcards. While postcards are often seen as promoting favorable feelings, some images from this archive cannot be seen in this same light. Of the 491 postcards in this collection, a handful of them portray images of Native Americans, and not in a positive manner. Three depictions of Native Americans in particular provide clear examples of exploitation. The pictures found on the three postcards present the stereotypical image of ’the Native’, favoring the United States’ historically dominant view of Native Americans. The use of exploitative images on postcards allows white society to continually benefit from these images through profits from stamps, their contribution to erasure, and their enforcement of white society’s stereotypes.

Postcards as an Entertainment Product

Postcards began their boom in the mid-1800’s when the United States Postal Service introduced them into circulation. However, these weren’t the same eye-catching pieces that you would expect; these early postcards did not feature a picture. This is because postcards were not originally intended for individual consumption, but instead were a means through which businesses could advertise themselves. 1 Rather than being the entertainment product that postcard collectors seem to view them as today, postcards were seen as an avenue through which businesses could make a profit. Around the 1890’s, these unique forms of communication would shift to the contemporary form of postcards: ones that have an image. These would become so popular that, in the year 1913 alone, the United States Postal Service documented that they had managed 968 million postcards. 2 This means that if each stamp was worth at least one cent during this time, then the government would have made over $9 million from mailing postcards alone.

Postcard from 1910, with Seal of the Territory of Oklahoma

Postcards and People

Nowadays, postcards have completely shifted away from the 1800’s advertising medium, transforming into vacation-oriented tourist paraphernalia. During times when travelling was not commonplace, however, the United States Postal Service connected families and friends in ways vehicles could not. Postcards took on a variety of meanings, providing the flexibility needed to communicate messages of varying levels of importance. Cards predominantly offered well wishes, holiday greetings, baby announcements, or even news of a death. The addition of pictures raised the status of postcards above letters, establishing them as both a form of entertainment as well as a means of communication. In thinking of postcards as entertainment, though, it is important to note who was selling the pictures in these scenarios, and whose picture was being bought.

Depictions of Native Americans on Postcards

In trying to understand these three specific cards from Oklahoma, it helps to know how nations which were not native to this part of North America ended up in Oklahoma. This history of dispossession further illustrates postcards’ promotions of the United States’ stereotypes.

When Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, “some 60,000 Native Americans were forced westward into ‘Indian Territory’” 3. This dispossession removed nations including the Chickasaw, Seminole, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Muscogee from their native lands, into land supposedly set aside for them by the government 4. These nations—known colloquially as “the Five Tribes of Oklahoma”—were forcibly moved to what became Oklahoma, the “final destination of the trail of tears” 5. Despite their forced displacement, Native Americans took steps to preserve their identities. One example of this can be seen through the Cherokee Nation’s response to the Indian Removal Act. The Cherokee Nation established a newspaper as well as took their case to the Supreme Court where they eventually won. Unfortunately, Andrew Jackson disregarded the Supreme Court’s decision and “Cherokee people were forcibly taken from their homes.” 6 Knowing this history of exploitation it becomes possible to see the images on the Oklahoman postcards as an extension of that history. The following three images can be seen as exemplifying three types of exploitation, all of which endorse negative stereotypes.

Financial Exploitation

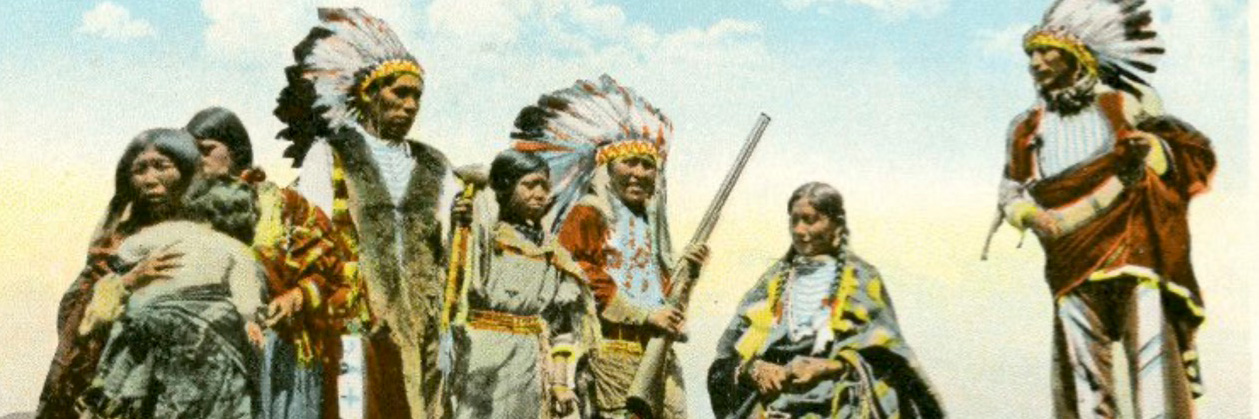

(Figure 1) 1910 postcard displaying a group of Native Americans

The first postcard (Figure 1) shows a group of eight Native Americans in Oklahoma with the generic title: ‘Indians on Miller Bros. 101 Ranch’. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, this ranch was occupied by George Washington Miller and “earned most of its notoriety from the wild west shows that it staged.” 7 Based on this information, as well as the clear staging of this image, it can be inferred that the people on this postcard were actors in these pageants. Moreover, the postcards were used as advertisements for such shows. This use harkens back to postcards’ original purpose in promoting different businesses, in this case, a wild west show. In these pageants, Native Americans were costumed to fit a certain generic look, one that affirmed the dominant stereotypes of the United States.

White people in power have historically profited by taking Native American’s land, and this postcard demonstrates that the exploitation extends to Native American images as well. Not only were white people directly profiting from the success of these wild west shows and the generic depictions of Native people in them, the government was indirectly profiting as well through the postage paid to mail the postcards. These varying levels of financial exploitation fostered negative stereotypes of Native Americans which upheld the United States’ dominant view.

Exploitation by Erasure

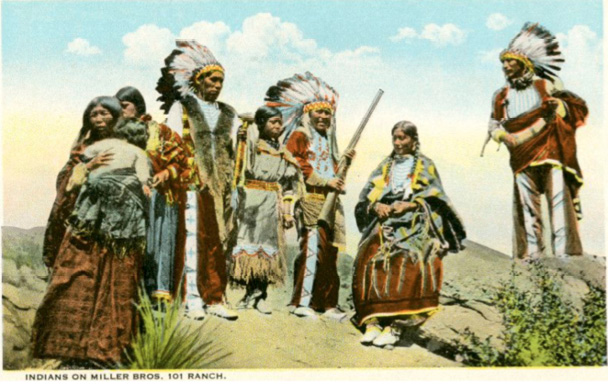

(Figure 2) Circa 1920 postcard Featuring a Native American mother and child

The second postcard (Figure 2) also displays this same type of United States stereotype, this time promoting erasure. On this postcard, the picture shows a Native American woman carrying a child photographed at the same ranch as the previous postcards’ image. The title at the bottom of this specific postcard reads, “Indian Squaw and Papoose” on Miller Bros 101 Ranch". The inclusion of such derogatory terms to describe a Native American mother and child are not only demeaning and inappropriate, but also a generalization. This is akin to the prior postcard which grouped eight individuals as ‘Indians’, as opposed to sharing any information about which tribe or nation they belonged to. Similarly, the second postcard also has no defining words in the title which describe who these people were or which nation they belonged to. This postcard contributes to the erasure of specific tribes in favor of universalizing the term “Indian” or, in this case, slurs for a Native American woman and her child. Since this woman was probably an actor on this ranch as well, it is important to note that these shows often perpetuated marginalizing depictions by casting them as showdowns between ‘cowboys vs Indians’. This theme seen throughout wild west films further subscribes to the erasure of individual groups and encourages this false idea of Native Americans not only being one group of people, but also being the enemy. Such enforcement of stereotypes endorsed white society’s views through postcards’ images, while at the same time aiding in erasure.

Exploitation through the White Gaze

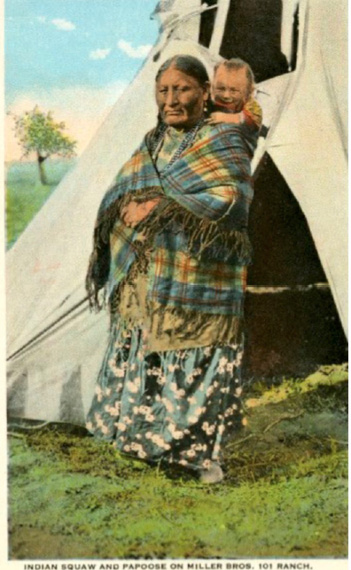

(Figure 3). 1941 postcard depicting members of the Pawnee Nation

In the third and final postcard (Figure 3), a group of Pawnee people are showcased. While their affiliation is included in the title, they are depicted in a way that conforms to white society and United States’ stereotypes. Despite this postcard not being set on the same ranch as the other two, it still looks staged in the way that people are posing. Presumably, the primary audience for this image would be white, as they would be the ones buying these postcards, and the images they bought would affirm white culture’s stereotypes concerning what a group of Native Americans should look like. Those encountering the photo would see the image postcard sellers know will make a profit: a group of stereotypically staged Native Americans. The commodification of images of the ‘generic Native’ through postcards endorsed United States’ stereotypes of Native American people, all while profiling one tribe or nation to be the same as all others. Despite the inclusion of the name Pawnee in the title, the commercialization of images of the Pawnee after they had been relocated from Nebraska displays the inherent exploitation of Native people, affirming the United States’ dominant stereotypes through the lens of white society on a postcard.

These three postcards depict Native Americans living in Oklahoma both as physically and literally one-dimensional, enforcing the stereotypes held by United States society. Postcards’ exploitative intentions to perpetuate these stereotypes contribute to erasure and enforce looking at Native Americans through a white perspective. For these reasons, these postcards exist as a specific form of propaganda, as they publicize damaging stereotypes of Native Americans through an entertainment beloved by United States’ society.

In contrast to the harmful ways in which these Oklahoman postcards depict Native Americans, the Pawnee Nation’s website includes galleries of their own images, which they deem to be representative of themselves. These pictures feature images from Pawnee Homecomings and community gatherings, as well as Pawnee City Council meetings. While the Oklahoma postcard’s supported white society’s stereotyping of Native American people, the Pawnee Nation’s website represents the nation’s lived reality.

Even now, the first sentence of the Oklahoma Historical Society page titled American Indians reads, “American Indians living in Oklahoma have a complicated, interesting, and unique history”

8. These adjectives trivialize the plight of nations that were dispossessed of the places they had called home and forced to move to Oklahoma. Further, these three extremely vague adjectives do not mention that Native Americans persevere despite everything that has been wrongfully taken from them, including the control over their own images.

Resilience in motion. Members of the Meskwaki Nation keep their culture alive–and authentic–at their Pow-Wow in 2020. Photograph by Jon Andelson

1 Jeffrey L. Meikle, Postcard America: Curt Teich and the Imaging of a Nation, 1931-1950 (Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press, 2016).

2 Ibid.

3 History.com Editors, “Andrew Jackson Signs the Indian Removal Act into Law - History,” History.com, August 30, 2021, https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/indian-removal-act-signed-andrew-jackson.

4 “Manifest Destiny and Indian Removal - American Experience,” Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed March 21, 2023, https://americanexperience.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Manifest-Destiny-and-Indian-Removal.pdf.

5 Pam Cornelison and Ted Yanak, The Great American History Fact-Finder the W.H.O., What, Where, When, and Why of American History (Boston , Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 2004).

6 “Trail of Tears,” The Museum of the Cherokee Indian, September 16, 2015, https://cherokeemuseum.com/archives/era/trail-of-tears.

7 Larry O’Dell, “Miller Brothers 101 Ranch,” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entry=MI029.

8 Fixico, Donald. “American Indians.” Oklahoma Historical Society | OHS. Oklahoma Department of Libraries. Accessed April 30, 2023. https://www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry?entryname=AMERICAN+INDIANS.