Holistic Care

My long-time patient, Mary, an 84-year-old woman, is bought to my office by her daughter Susan. Several weeks before this, Mary had been hospitalized for congestive heart failure, her 5th hospitalization in the last 6 months. She and her daughter are asking for advice. I ask Mary and then her daughter to talk about their concerns. I can already see that Mary looks much frailer than when I last saw her a month ago. She needs assistance getting up on the exam table and I notice that her leg edema has gone from 2 to 3+. 1 Her daughter looks fatigued and depressed.

Mary says she’s always very short of breath despite her oxygen use. She has frequent angina with any activity. When she confides that she thinks she’s near the end of her rope, Susan sheds a few tears. Mary wonders if she’ll still have to keep returning to the hospital for the rest of her life. Her daughter asks if one of the new heart failure drugs advertised on TV would help her mom. She has temporarily moved from Omaha to live with her mother and does not want to put her in a nursing home if it’s possible to avoid it. She agrees that her mother has failed a lot over the last several months.

As her family doctor, I know that we have already discussed end-of-life care and that she has already made out her living will and durable power of attorney. We have already discussed hospice, and now we discuss how it may best fit with her desires and values. I know that her husband John died several years ago and that with her strong religious beliefs, she is actually looking forward to being reunited with him in the after-life. I know that Susan is her only child and that she is getting burned out caring for her mom. I am aware that the family is just on the edge of financial survival, especially with Mary’s out-of-pocket costs for her many drugs being over $1600 a month. I know that she has lived on her farmstead for over 60 years; I have made home visits there in the past. We then discuss my recommendations. I suggest that she go on hospice. I tell them that she can most likely be kept at home with the support of hospice personnel. She won’t have to see the heart doctor in the big city since that doctor really won’t have anything to offer. I suggest that she should probably not come to the office anymore, not only because it is difficult for her to get out, but also because she may be exposed to sick patients in the office. Nor does she need to go to the emergency room, where she may have to wait hours and then be seen by a physician who is not familiar with her situation. I tell her daughter Susan that the drug “E” that she saw advertized on TV is a relatively new drug, has been tested on a small number of patients, has a marginal benefit, and will cost them over a thousand dollars a month, since her insurance won’t cover it. I also know that Mary has significant kidney failure and that this drug could actually make her heart failure worse.

I know that Mary loves dogs and that her beloved Rex, whom she had for 13 years, died two months ago. Mary was a long-time piano teacher and loves music. I arrange for a therapy dog and a music therapist to visit. Hospice will enlist volunteers to visit Mary to allow Susan to get out periodically for her own health and wellbeing. Finally, I tell them that besides the hospice nurses, I can and will make home visits whenever needed. I give them my cell number and tell them to call me for anything, any time, day or night.

Three months later, Mary died peacefully at home with her daughter and friends at the bedside.

As a recently retired family practitioner, I predict that the kind of medicine that I practiced, exemplified by my interactions with Mary, will soon go extinct. We family physicians are going the way of the dodo bird, passenger pigeon, and the dinosaurs. We will go out not with a cataclysmic bang, as the dinosaurs did 65 million years ago, but through retirements, attrition, market forces, and fewer new doctors going into the specialty. I am not a disillusioned romantic, bemoaning the passing of “the good old days” in medicine, but a realist witnessing the loss of a model of medicine that has long benefited both patients and providers.

Having witnessed these changes over almost half a century, I am in a good position to chronicle the seismic changes that have occurred in medicine in the United States over this time. My experiences in small-town rural Iowa are a microcosm of the entire healthcare system.

Mary spent over 60 years on her family’s farm, and I see parallels to the gradual disappearance of the diverse farms of the past as these small entities face the socioeconomic forces of “big ag.” An earlier article in this periodical by Dan Weeks chronicled the dissolution of small businesses on Main Street in many rural towns and cities. In my view, the nearly complete control of our political system by big money and political lobbying has been a cancer, not only on medicine but on agriculture.

I realize that the family doctor or family practitioner I will describe may be unknown, unfamiliar, and even incomprehensible to many people. Many big city folks have never been treated by a family practitioner but rather have always been seen by an array of specialists, either in the office or in the hospital. To those people, the concept of a single doctor treating 80 to 90 percent of maladies, let alone making a house call, would seem unbelievable. However, many Americans of retirement age watched the TV show Marcus Welby, MD, starring Robert Young. It aired on ABC beginning in September 1969, and ran for seven years, becoming for several years the most watched television show in the country. As a compassionate general practitioner, Marcus Welby was the quintessential family doctor and friend. He was always close to his patients. He and his young assistant, Stephen Kiley, tried to treat patients as individuals although they were living in an age of increasing specialization and indifferent physicians.

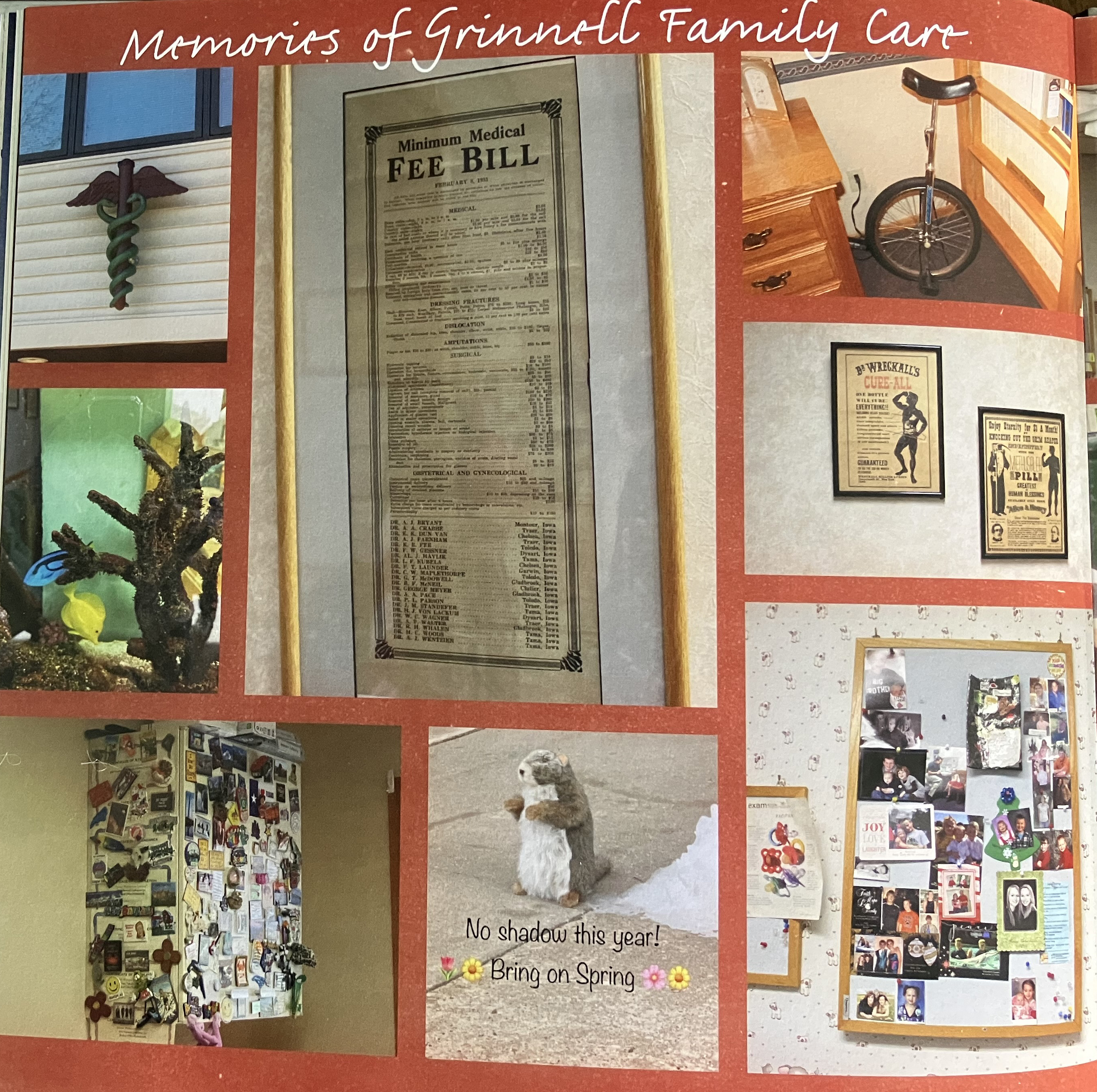

Memories of Grinnell Family Care.

When today’s older generation was growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, many primary care doctors (pediatricians, internists, and general practitioners) had offices in their homes and made home visits if needed. I vividly remember my pediatrician making daily visits to our home to give me a big injection of penicillin in my behind every day for two weeks. I had received a severe burn, and the antibiotics were injected to prevent it from getting infected. Emergency rooms, especially smaller ones, were not usually staffed by physicians, although one would be on call for each specialty. If you cut your hand, you went to your doctor’s office for sutures. These doctors were paid in cash and were often quick to refer patients to specialists. These medical warriors made a decent living, but they worked long hours, most continuing to work until they died or could no longer practice. I remember as a college student coming home over Christmas break to have my eighty-plus-year-old ENT remove my tonsils.

A New Specialty

In the 1960s, it became clear that the traditional general practitioner (GP) practices were failing because of the rapid increase in medical knowledge and the growth of other specialties. To be certified as a GP required only one year of a rotating internship to complete training. In 1966, the American Medical Association released the Millis Commission Report 2, which called for a new, better trained cadre of comprehensive physicians that could treat the majority of medical conditions. The report asserted “that illness is usually not an isolated event in a localized part of the body, but is a change in a complex, integrated human being who lives and works in a particular social and family setting, who has a biological/psychological/social history. What is needed and what the medical schools and teaching hospitals must try to develop is a body of information and general principles concerning man as a total, complex, and integrated social being.”

A new specialty emerged called Family Practice. It required a vigorous three-year training program in a certified residency and certification of physicians by board exams to be sure that the new training goals were met. The Board of Family Practice was established in 1969 and by 1976 there were over 300 approved residencies.

My Journey

Although after college I thoroughly enjoyed teaching both elementary and secondary school and getting a master’s in science education, I realized that my true interests lay in philosophy and the history of science. While considering a career as a PhD in philosophy of science, I realized that at that time there was a glut of PhD’s in the US. I then considered the profession of medicine, which I felt was “applied” philosophy of science. To me, being a doctor meant becoming one like Dr. Welby, a holistic practitioner in the relatively new specialty of Family Practice. So, I also applied to medical schools.

I was fortunate that my medical school, Michigan State University, was a relatively new school whose mission was aimed not toward training specialists or future researchers, but toward training primary care doctors. It emphasized a holistic approach to patients in medicine. Although the new field of Family Practice had lofty goals, the rest of medicine, particularly the specialties, were often antagonistic toward the field for a number of reasons, not the least of which was economic. FPs delivering babies, setting bones, doing surgeries, (for which they were trained), and managing patients in the hospital, took away from their bottom lines. Many fought against the fledgling specialty, but nonetheless, in the following decades the specialty grew, and by 2000, there were 70,000 family practitioners, with 91 percent being board-certified.

Board certification requires: proof of greater knowledge and experience in a specialty; performance and procedure documentation; the passing of a certification examination; as well as a requirement for more than the minimum required continuing medical education required by each state for licensure. However, it soon became a requirement by hospitals and medical clinics for staff privileges. Originally most boards did not require re-certification but granted it for life. The Board of Family Practice was the first specialty to require recertification every seven years. They realized that since medicine is constantly changing, what was true seven years ago probably would either not be true today or else would be significantly modified. For the family practitioner, this required not only comprehensive written exams covering all areas of Family Practice, but also submission of office records and modules of office procedures and data from real life.

During our last year of medical school, we all had to choose what specialty and residency we would apply to. I chose Family Practice because it completely agreed with my goals and values. Next was the choice of residency. Most were based in university or teaching hospitals.

Thus, they were training specialists as well as family practitioners. At that time – and it continues today – Family Practice is put last in the pecking order. The prejudices held in academia and by specialists made FPs feel that they were at the bottom of the specialty ladder, receiving the least respect and fewest resources. For example, on cardiology teaching rounds in the hospital, there is a long-ordered line, starting with the cardiology clinical professor, cardiology fellows, cardiology residents, internal medicine residents and fellows. Last came the FP residents, and medical students. Who do you think got the best cases, most attention, questioning, and teaching?

In 1978, after a thorough search, I chose the Family Practice residency in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. It seemed the best residency in the country at that time, and it lived up to its reputation. As the only residency in the city, we served both hospitals, St. Luke’s and Mercy. All the doctors training us were intent on giving us the best experiences and education possible. I was a first assistant on open heart and brain surgery, delivered more babies than the OB residents at the University of Iowa, and took more orthopedic cases than the ortho residents at the University.

Grinnell was a community that referred patients to Cedar Rapids hospitals. Highly recommended by one of my role model professors, Dr. Galbraith, Grinnell offered everything I was looking for in a future practice and community. As a doctor in this community, I would also have an opportunity to teach and proctor first year Rush medical students from Chicago. When Dr. David Ferguson offered me a position in his practice, I jumped on the opportunity. As a well- trained FP physician, I was able to do everything that I was qualified and trained to do, both in and out of the hospital. With further board certifications in sports medicine, hospice and palliative care, I could “practice” medicine, literally from birth to death.

Family Docs in Grinnell

At that time, 1981, each of Grinnell’s Family Practice doctors were on a rotating call for the hospital emergency room, including nights and weekends. We delivered our own patients’ babies and took care of the newborns, and moms and were the primary care doctors for all hospital admissions. We consulted surgeons, internists, orthopedists, and other specialists as needed, but saw and managed our patients daily in the hospital. We had a strong family practice section in the hospital, with up to 11 FP physicians on staff at one time. One of the major health goals of our community was for everyone to have an FP physician. A FP could and would usually take care of everyone in the family, literally from cradle to grave, from newborn to old age. It included: Ob/gyn; pediatrics; internal medicine; surgery; and geriatrics. Referrals to the specialists came only from the FPs, and after seeing the specialist, patients would come back to their primary care doctor. Many of us assisted with surgery and could provide the surgeon with the personal, medical, and family history of the patient if needed, as well as being present with the surgeon in the post-op family conference.

As the hospice medical director, I often got referrals from the FPs at the patients’ end of life. I was chosen as the hospice medical director because of my strong interest in end-of-life care and because I had become board certified in the new specialty of Hospice and Palliative Care. We managed as many patients as possible at home or in our newly designated hospice rooms in the hospital, if the patient’s symptoms could not be managed adequately at home or if the family was becoming too exhausted.

Grinnell Family Care Staff.

Looking back, I can honestly say that the doctors set the practices, policies, and rules for the hospital. The goal was always what was best for the patient and their families. The hospital administrator and the board had a synergistic relationship with the medical staff. Communication was generally excellent among the physicians. Doctors congregated in the doctors’ lounge before or after rounds. We saw our colleagues daily, not only to discuss cases, but to interact socially. As FPs we communicated among ourselves and had journal club meetings at our own homes. We would meet monthly at a different physician’s home, meet their family, have snacks, and then discuss various topics and articles over a wide range of topics. If one of us was working at the ER and a question or concern arose about another family practitioner’s patient, we just called and discussed the best course of management and follow-up. The FPs would gladly “cover” for one another so that we could attend a child’s concert or sporting events or get out of town or even just take a long jog outside of the hospital. I don’t ever recall hearing the term burnout.

Changes

I think the first indication of major changes to come, for not only family doctors but all physicians, came in 1984. Most FPs either owned their own practice or were part of small groups, independent of the hospitals and other large organizations. At that time, although insurance companies, Medicare, and Medicaid couldn’t and didn’t tell you what to charge, they effectively determined the charges physicians could make by telling you what they would pay for or reimburse. I could no longer give free or greatly reduced charges to indigent patients or those without insurance. I vividly remember seeing a young boy from Alaska who was brought in by his father with a fishhook embedded in his eyelid. The family would come to Iowa each August with a truck full of fish and return with a truck full of sweet corn. Since he had no insurance, I surgically removed the hook for three fillets of salmon. Likewise, many Grinnell College students were from out of state and often their insurance would not cover treatment in Iowa because they were “out of network.” Usually, our practice did not charge them. I kept quiet about this and never reported these surreptitious encounters.

The Small Town FP

During my third year of residency in Cedar Rapids, I was required to do a three-month rotation in Mechanicsville, a small rural Iowa town about 35 miles from Cedar Rapids. The residency owned a large farmhouse, and residents and their families were to move there and become the family doctor for the entire town. I saw patients in the clinic, in nursing homes, and at patients’ homes. The medical residents played on the softball team, participated in the Kiwanis Club, served as school health educators, and were even expected to host the annual hog roast for the entire residency. This rotation exposed residents to what small town rural life and practice would entail. Although I eventually settled in a town of 9000, the relationships were the same. I would take care of my auto mechanic, my banker, and my children’s teachers, and see them in the coffee shop or at Walmart. Since I practiced for 42 years, I often took care of my patient’s parents and grandparents, and delivered their children. I knew their personalities, likes, prejudices, hobbies and financial situation. I confidentially knew their mental health, and their deepest concerns, fears, and joys.

Of course, the trust this required was forged during interactions over many years and decades, both in and out of the office. Grinnell’s family doctors spent time with our patients, who determined the agenda for the visit. We were often there for the birth of their children, and, at the end of life, we were often with them and their families as they transitioned from this world to the next.

Times of Transition

The scope of family practice underwent a drastic evolution over the next few decades.

First, although helping bring a new life into the world is one of the greatest joys a physician can experience, and early in my career, most family practitioners delivered babies, many eventually decided to give up this part of their practice. For many, the decision was driven by the strain of always being available and on call for the event, whether during office hours, in the middle of the night, or on Christmas day. It was at times exhausting. After the hospital in our town recruited an OB/GYN doctor, only a handful of family doctors elected to continue doing OB.

Second, the hospital began hiring residents from the teaching institutions to cover the ER on weekends, a change which, at the time, we all applauded. In 1979 the specialty of emergency medicine was formed and, within a decade ER doctors took over night and weekend calls completely. Like all double-edged swords, though, this change cuts both ways. It was a blessing to get more sleep and not to have the office disrupted on busy days. On the other hand, the ER physicians usually did not know either our patients or the community well. They seldom called us for consultations or to seek advice on managing our patients.

Third, Grinnell Regional Medical Center (GRMC), the previously nonprofit, independent, community-owned small hospital, was taken over by a large for-profit healthcare system, Unity Point. National economic trends within the healthcare industry and political system, coupled with COVID, made this change almost inevitable.

Up to this point, GRMC had achieved national status and recognition not only for its excellent medical care, but for the development of cutting-edge surgical procedures, integrative medicine, and research. GRMC became one of the earliest centers for bariatric surgery, even before Duke University. In collaboration with Grinnell College, GRMC did cutting edge research on infection control by installing copper alloy metals in both the operating suites and patient rooms. Music therapy was integrated into many aspects of patient care and community-created art hung in the hallways and patient rooms. Our independent hospice was thriving both in and out of the hospital. Although Unity Point first espoused local control by the hospital board and doctors, its policies morphed into complete domination. The de facto model was essentially, “It’s our way or the highway… or… “That’s what we do in Des Moines.”

As part of this transition, inpatient hospital care was gradually taken over by a new class of doctors, called hospitalists. These physicians took care of patients only in the hospital, had no office practices, did not know their patients like the FPs did, and importantly, became employees of Unity Point. Family physician care of inpatients was at first discouraged and finally prohibited, except in OB. Within a short period of time, the community FPs, medical staff, and hospital board no longer controlled the fate or direction of medical care in our community.

Hospice

Like most FPs across the country, we in Grinnell had our previous hospital practices diminished or terminated. I thought my hospice practice, which the local community had started as one of the first small rural community hospice programs in Iowa 38 years earlier, would be safe from the large healthcare system. However, it was not.

During the first year after Unity Point acquired our hospital, our community hospice—which provided excellent care and was financially solvent—was left alone. But then administrators started dictating what things I or my nurses could or could not do, what drugs we could use, and what my nurses could or could not carry in their bags to home visits. In addition, they started requiring all of us to do mountains of paperwork. They wanted me to keep a log of every minute I spent related to hospice care. This was in spite of the fact that I was or had been on call 24/7/365 for an average of over 20 patients at a time for over three decades and, had been twice board-certified in Hospice and Palliative care. Unity Point also told me I could no longer care for inpatients in our previously designated hospice rooms. If a hospice patient’s symptoms could not be adequately managed or treated at home, or if their family or social support became exhausted, we hospitalized them locally rather than transferring them to a different facility or hospice house in another city. Finally, since I could no longer take care of hospice patients the way I felt they needed to be treated, I resigned as hospice medical director.

Electronic Medical Records

In my opinion, electronic medical records (EMRs) have been responsible for cataclysmic changes in medicine. Like the smart phone, the EMR can confer tremendous benefit as well, through standardization, allowing easy storage and transfer of data from one provider or institution to another, creating templates for histories, diagnosis, and suggesting algorithms for treatment. In addition, such records could be accessible from anywhere in the world.

However, these systems were designed by computer techs and businessmen rather than by doctors. Different and competing systems were developed which often couldn’t, or wouldn’t, talk to one another. The costs for implementation were huge for physicians’ offices and exorbitant for hospitals and large healthcare systems. In addition, the systems were constantly changing and updating. Originally, they were optional, but soon the government and third-party payers began requiring them for “metrics”. The things measured included clinical satisfaction; patient satisfaction; technical performance; visit volume by modality; and overall reimbursement by modality. Over time almost all hospitals were using them, and physician offices were penalized financially if they didn’t have them. In 2010, 16 percent of hospitals and 28 percent of physician-based offices were using them; by 2020, 96 percent of hospitals and 78 percent ofprivate offices had implemented an EMR. My clinic never switched. As providers we and the patients set the agenda for the office visit, and then dictated what we felt was important and needed for the medical record after the visit. The typed notes were on the chart, usually within 24 hours. However, our office did have to accept financial penalties for not complying.

Many physicians now feel that EMRs have harmed the relationship they’re able to have with their patients. Despite their usefulness, particularly within specialty care, EMRs cannot capture the psychological, social, and spiritual character of a person or their illness. Touted as a timesaver, they have had the opposite effect. A 2022 study by the Mayo Clinic found that physicians spend about 50 percent of their office and hospital time working on EMRs, rather than on direct patient care. Many physicians now spend many extra hours at night and on the weekends completing these forms. No wonder EMRs are cited as a major cause of burnout by most primary care providers.

Another major factor in physician burnout is loss of autonomy. As more and more FPs and other doctors are bought out by or choose to work for a healthcare system, they are now under the control of a new boss. They no longer have a say in how much time they spend with the patient, what metrics they must get and record, and what they can and cannot do. Disillusioned, many family practitioners question why they are still in this profession at all. Many retire early, leave primary care, leave the profession altogether, or worse. Physicians have the highest suicide rate of any profession; one of my partners committed suicide in his 30s.

Closing My Office Practice

I thought I was safe in my independently owned office practice, as I was still able to run it the way we had since its inception. Despite being 75 years old, I still enjoyed practicing medicine, and I could have continued for several more years. However, three factors led me to close my practice.

First, five of my staff, who had been with Grinnell Family Care for decades, were either approaching 65 or were already there and ready to retire. No new employee could replace their patient knowledge, positive relationships, and loyalty to our style of practice.

Second, decreasing reimbursements, especially from Medicare, combined with my aging clientele, resulted in an actual financial loss my last two years of practice. I took home a salary less than that of any of my employees.

Third, it became impossible to recruit newly minted family doctors. They wanted nine-to-five hours, no night or weekend call, no nursing home responsibilities, no OB or ER work, and certainly no hospice call or home visits. After a year or more in practice, none would want to buy into a practice, partnership, or clinic. When asked what they expected for starting compensation, they asked for more than I was making after 40 years of practice, and they often wanted me to pay off all their student loans. When asked how they came up with these expectations, they replied that large healthcare systems were making these offers.

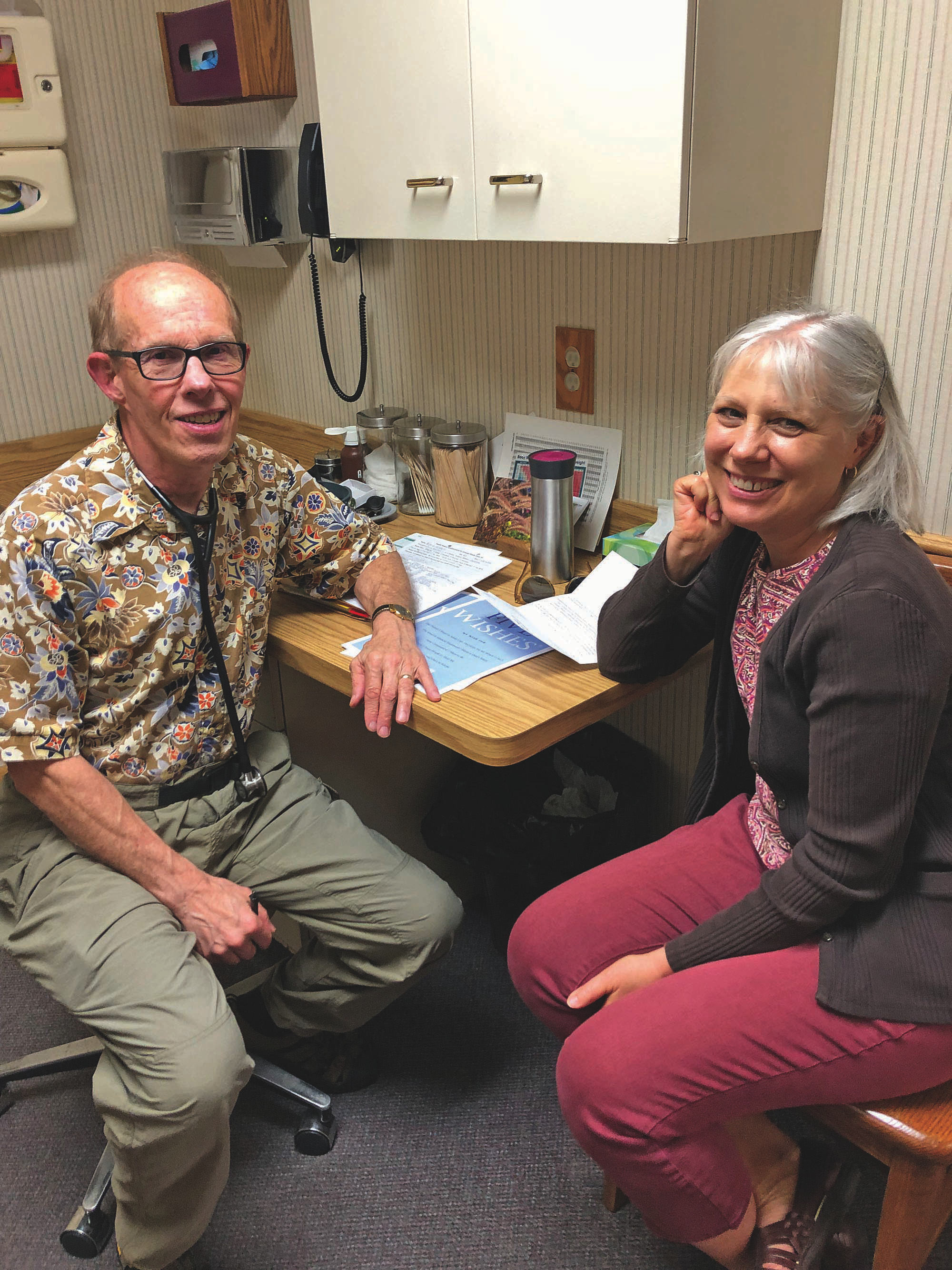

Dr. Paulson seeing his last patient.

As it became clear that I would have to sell the practice, I reached out to a number of healthcare organizations in the area, including the University of Iowa. No one was interested in buying a large, respected, four-person practice and clinic. Hence on July 1, 2023, I had to close a half-century old family practice.

The Future

These are the realities of medical practice today.

When a family doctor or internist spends over an hour with an elderly patient with multiple, complicated chronic medical problems amid serious social, economic, and psychological issues, that doctor gets reimbursed a tiny fraction of what a “specialist” gets for quickly treating a chronic skin lesion with liquid nitrogen or spending five minutes with a patient complaining of knee pain.

In addition, preventative medicine does not make money for big health care networks. Hospitals profit from short office visits, tests and X-ray or CAT scans, and procedures, and by referring patients to specialists. Instead of hiring residency-trained FP’s, hospitals improve their bottom line by hiring less-well-trained, although often good, lower-level providers.

He waited too long to retire.

The traditional family doctor—that is, a doctor who manages most of the patient’s problems, who knows the family, who spends time with the patient, and who emphasizes preventative and holistic care—is going extinct. Beside the issues of the EMR, autonomy, and burnout, the current economics also make the model of the family practitioner problematic.

Conclusion

I will conclude by returning to what I said earlier, comparing medicine and agriculture. Just as the traditional family doctor is disappearing from the landscape, so is the multi-crop, multi-animal, integrated family farmer. More and more, huge economic and political forces control both farming and medicine. Any honest observer can see that both are headed in unsustainable directions. Unfortunately, I see no quick fixes for either. Unless there are significant changes in our current political system, the future is not hopeful for either.

R.I.P. Family Doctor

1 https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/12564-edema

2 The Graduate Education of Physicians: the Report of the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education, Commissioned by the American Medical Association Council on Medical Education, 1966, 114 pages. Pgs 45, 51