From its opening on December 31,1902 until its doors slammed shut for good on December 20, 1933, the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians had become a symbol of misery, negligence and abuse. Even today the phrase insane asylum has overtones of horror. For the disenfranchised people who were detained there at the convenience of the U.S. government, it was a place of dread which Native peoples could never have put a name to in their own language. During its operation, the facility provided problematic mental health care to almost 400 patients—only nine of whom had ever been legally committed through a court.

I first came across the Canton Asylum while casually looking on the internet for information about insane asylums in general—places I had mostly associated with Victorian England. I was surprised to learn that these establishments had been as prevalent in the U.S. as they were overseas, and was particularly astounded to see one that specialized in Native American care.

The idea of an asylum for Indians seemed too bizarre to be true, and the snippets of information I saw were almost as puzzling as the idea. At the time there wasn’t much to go on—just a few essays and a few quotes from a government report. I couldn’t get the place out of my mind, though. I reasoned that the report authenticated the place and would be enough to jumpstart a deeper search. That’s when I began the long, long process of following the clues and pathways that eventually led to my book, Vanished in Hiawatha: The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2016).

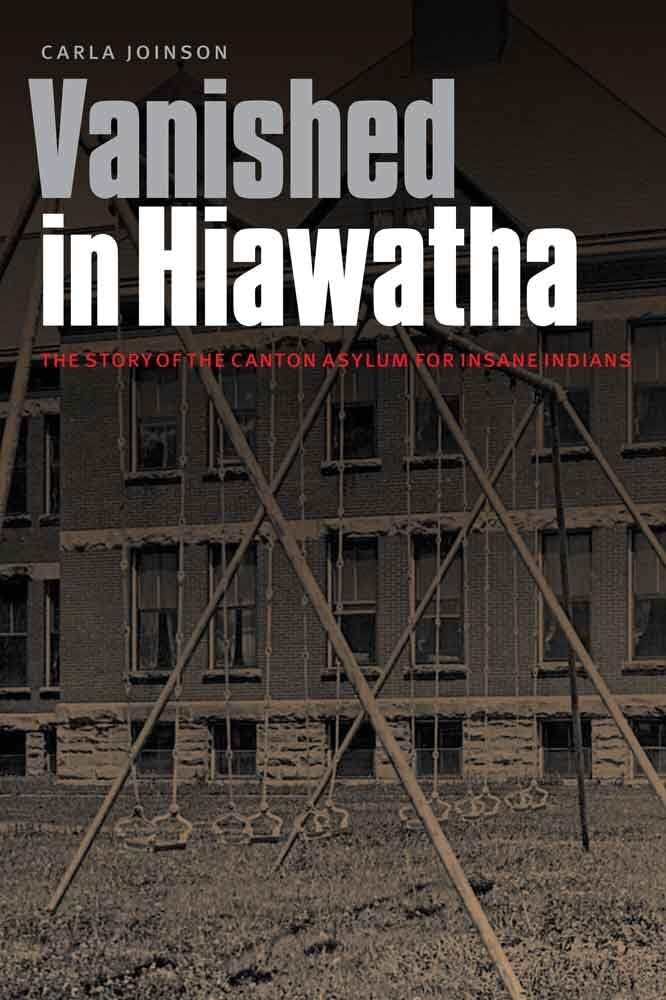

Cover photo from Vanished in Hiawatha: The Story of the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians.

When Indian agent Peter Couchman first suggested an asylum specifically for insane Indians in 1897, it really didn’t seem to be such a bad idea. Native peoples were wards of the federal government at the time and faced prejudice on many fronts. They certainly were not welcome in state hospitals already hard pressed to provide services for their non-indigenous citizens who, incidentally, could vote. Why not create a centralized hospital for these unwanted and powerless people who were already on reservations under federal oversight?

Considering the paternalistic attitude toward Indians prevalent at the time in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (almost exclusively referred to as the Indian Bureau) and among lawmakers in Washington, surprisingly few people embraced this suggestion. Most of the supervisors and agents working on reservations held that insanity was quite rare among Indians and that the cases that existed were relatively mild.

To put this in perspective, one reservation superintendent looked at his population of nearly 6,500 people and reported that not one was insane. The Indian Bureau didn’t need its own asylum. A survey by the pro-asylum Commissioner of Indian Affairs bore out this view: at the time, just seven Indians were being treated at institutions around the country. In another survey, the Committee on Indian Affairs scraped up “fifty-eight insane Indians, one doubtful, six idiotic, and two partly idiotic” who might require treatment.

Unfortunately, practical observations about the need for an asylum by men in the field didn’t trump the “boosterism” prevalent in small towns eager for projects that would enhance their status or grow their economies. South Dakota senator Richard F. Pettigrew thought an asylum would be great for South Dakota, and as chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs he had the clout to help push it through. He also knew the perfect person to run it: former congressman and ex-mayor of Canton, South Dakota, Oscar S. Gifford. In turn, Gifford believed Canton would be the perfect site for the asylum and convinced Pettigrew of it. So it was that when the first patient arrived at the new federal insane asylum, Gifford—-an attorney with no background in medicine—-was in charge to welcome him to it. Dr. John Turner was the facility’s assistant superintendent.

Anyone digging through the origins and setup of the Canton Asylum (also known locally as Hiawatha Asylum) could predict it wasn’t going to go well. And of course it didn’t. There weren’t many problems at first, considering the asylum had new buildings, very few patients, and the full support and backing of a town full of pride for “the only facility of its kind in the world.”

The Main Building at the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians, also known as the Hiawatha Indian Asylum. From the collection of the South Dakota State Historical Society.

Though he wasn’t a psychiatrist, Dr. Turner was a competent physician who unfortunately had to report to Gifford and accept his calls if they disagreed on an issue. Gifford failed to support many of Dr. Turner’s instructions for patient care while he was absent (often for days at a time) to pick up new patients in and out-of-state, and didn’t back him up with staff. The two finally clashed over the medical treatment of a patient. Gifford forbade an operation, the patient died, and Turner complained enough to get an investigation started. That ultimately led to the ouster of the superintendent, and Gifford was replaced by an actual psychiatrist, Dr. Harry Reid Hummer.

Though it might be thought that this would have resolved many problems, the quality of psychiatric care wasn’t the actual problem with the Canton Asylum for Insane Indians. Psychiatry was a relatively new field at the turn of the 20th century, and it would almost be laughable to read about acceptable treatments for insanity, if it weren’t so sad. Besides liberally used and sometimes horrific restraints, common treatments in most asylums included sedatives; purging through induced vomiting and bowel movements; water therapies that confined patients in bathtubs, sometimes for days; sheet wraps soaked in water that could likewise continue for hours or days; and static electricity sessions. The Canton facility didn’t seem to use these therapies excessively or at all and depended mainly on a few types of hydrotherapy and occupational therapy like sewing and garden work. Patients there received just about the same quality of care as patients in other asylums. The problem with the Canton Asylum always had much more to do with the Native American identity of its patients.

Even if the asylum had been filled with U.S. citizens, any doctor would have found it difficult to diagnose and treat patients who spoke a number of different languages which the hospital staff didn’t speak. During Canton Asylum’s history, more than 50 tribes were represented, and though many patients spoke English, many others did not or didn’t speak it well.

Equally important, Native cultures and practices—which differed even from tribe to tribe—were quite different from that of the medical community from which any doctor assigned to the institution would have hailed. Their ideas and those of the South Dakotan staff concerning appropriate (sane) behavior would have been based almost solely on mainstream U.S. cultural standards. Superintendent Gifford had spent many years in the West and did recognize and allow Native practices like dancing and singing. However, Dr. Hummer was an Easterner through and through. He knew nothing about his patients’ culture and had no interest in learning about it.

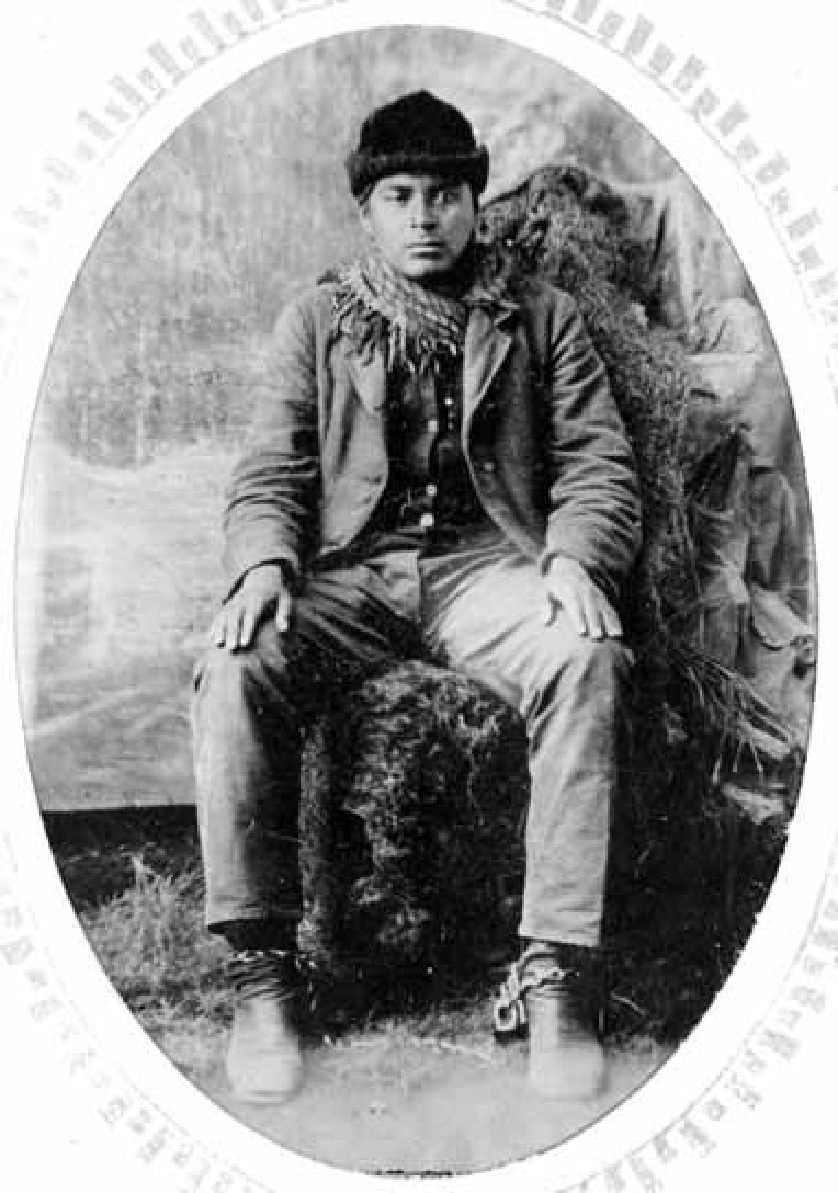

Photo of Arch Wolfe, in shackles circa 1893. Wolfe was a Cherokee man who was confined in multiple institutions, including the Canton Asylum, where he died in 1912. Photo courtesy of the Cherokee National Historical Society, Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

The attitude of the superintendent—-and for that matter, most of the Indian Bureau—-had consequences for patients. You can imagine the fear and disorientation they felt when they arrived at the Canton Asylum and staff went to work stripping, bathing, and de-lousing them. If patients wore Native clothing, it would be exchanged for “citizen” garments and men’s hair might be cut. To staff all these actions would simply have been practical entry procedures, but they would have cut the patients to the soul. Added to this, the asylum was also a tourist attraction that was open to visitors from 1 – 5 p.m. Wednesdays and Fridays.

This indifference to Native sensibilities had a long history by this time. The earliest settlers recognized the need to interact peaceably with Native peoples, but as they gained dominance that need began to fade. Because the worldviews of Natives and newcomers concerning property, lifestyle, and religion were so different, clashes became inevitable and Native culture was marginalized. Authorities failed to honor treaties with protections for Native peoples, and President Jackson’s Indian Removal Act (1830) provided the means to gather them onto reservations. Once there—cut away from their homelands and traditional lifestyles—authorities promptly denied Indians unapproved cultural activities.

By the time Canton Asylum opened in 1902, formerly independent tribes had become domestic dependent nations, and their peoples mere wards of the federal government. The good news was that after years of seeking to annihilate them, the U.S. government now sought to assimilate Indians into mainstream American culture. The bad news was that the new policy of assimilation had another sort of annihilation as its goal—-the erasure of Native customs and culture.

The government achieved part of its goal to stamp out Native autonomy and identity through an astonishingly cruel boarding school system. At least 60,000 children were taken away from their homes—sometimes through abduction—and required to live in boarding schools hundreds of miles away from their homes. These children were forced to speak English exclusively and to use the English names that the schools assigned to them. Many never saw their families again until they graduated, and at least 500 died from disease, abuse, and murder. In one incident, ten girls were stripped to the waist and flogged with a buggy whip for stealing a can of baking powder. Survivors told of solitary confinement, beatings, starvation, and forced manual labor. There were no champions for children, either.

The government’s policy was further expressed by its confinement of adults at poverty-level dependence on reservations. Both reservations and schools were overseen or subsidized by federal authorities who could make life-changing decisions for Native peoples—including whether or not they were judged to be sane. Procedures for committing a Native American to the Canton Asylum were simple: Someone in authority on the reservation decided the person was insane, checked with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to see if Canton could accept a new patient, and initiated commitment if the answer was positive. Patients would arrive to an open-ended stay at the asylum—all without a court order or its superintendent even examining the person first. The odds of victoriously fighting a commitment were certainly stacked against the Indian patient.

It’s worth noting that things weren’t much better for non-native mentally ill people elsewhere in the country. In many states a person could be committed to an asylum via a certificate from one or two doctors and a letter from a relative. By 1904 the Washington, DC metropolitan police could arrest and detain someone whenever two or more respectable citizens filed an affidavit saying they believed that person to be of unsound mind. Never mind how easy it was for a husband to commit his wife! Unless a person accused of insanity had a powerful ally, there wasn’t much hope.

Fortunately, as time went on, in the larger culture legal protections for people accused of being insane strengthened through the intervention of increasingly enlightened citizens, the testimonies of former patients who were willing to speak out about their experiences, and huge scandals. These protections didn’t extend to the Indian experience, though, and Canton Asylum’ superintendent continued to commit and treat patients with near autonomy.

The asylum was inspected at regular intervals like all federal facilities, but inspections concentrated mainly on the buildings, food, and administration. For all intents and purposes, Dr. Hummer could act without serious hindrance from anyone. Even the few inspectors who noted his slipshod management were thwarted by Hummer’s smooth rebuttal of their findings and the reality that no one else really wanted his job.

Dr. Hummer presents a curious case study. Though I could find various accounts of his clever dealings with inspectors and naysayers, I could find very little that spoke to his own feelings on any personal level. Inspection reports and interactions with peers and colleagues in the Indian Bureau seemed to indicate that Hummer felt a deep frustration running the institution. There was never enough money, or support, or staff to do the job adequately and these accusations are supported by the inspectors themselves. However, for all his complaints, Dr. Hummer seemed to prefer autonomy over everything.

For a short time, Dr. Hummer worked with Dr. Turner’s replacement, Dr. L. M. Hardin. Hummer managed to make Hardin’s life so miserable that he finally quit in frustration. After that Hummer fought tooth and nail against accepting medical staff, such as a second doctor, or nurses who might have made his job easier, but also would have brought in some accountability. He routinely pinched pennies on the most basic items so he could make a show of returning money to the government. He never asked for interpreters so he could interact more effectively with his patients. Worst of all, he failed to check on all his patients regularly to actively seek their welfare. Why? And what in the world kept this man tied to the Canton Asylum?

I can only look to his actions and theorize. When he first took the job, Dr. Hummer probably saw a wonderful opportunity. Running an asylum, even a small one, held a lot of prestige and might have led to leadership at a larger asylum. And of course, Canton Asylum was the only one in the world housing Indian patients exclusively. Hummer might have thought he’d first make a name for himself with research and case studies, then move on to bigger and better things. He did present a paper, “Insanity among the Indians,” at the 1912 Medico-Psychological Association meeting, but that ended up being the extent of his efforts in scholarship.

It seems clear that he was a man in love with authority, and at this faraway outpost he got a chance to exercise it unchecked. He resented any interference from even the most well-meaning observers, and he demanded complete loyalty from his employees. He additionally allowed himself to waste his time doing administrative tasks that could have been delegated. He allowed no one to answer the phone but himself and wrote all reports, took time to supervise construction projects and deal with such minutia as sending in coal samples. Inspectors noted this tendency and put it down to Hummer’s inability to pass authority on to anyone else.

Because he was the only psychiatrist on staff Hummer’s decisions were almost never challenged, an ideal situation for someone with a large ego. An inspector noted in 1909 that Dr. Hummer “considered it the rankest impertinence for the attendants to make any suggestions.” He could run Canton Asylum like a dictator and manage to fool most of the world into thinking he was doing a good job. Here again, his patient population was at a disadvantage. Few spoke English fluently, and most were uneducated. Some managed to send letters to relatives and even to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, but Hummer easily deflected any complaints or accusations patients made by pointing out that the writers were insane. There were no Native psychiatrists who could challenge him, and even the most loving relatives were hampered by language, distance, and poverty. Few patients received visitors who could raise a stink; they were left to receive whatever care the staff wanted to give them.

The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians was torn down long ago, and the place where it stood is now occupied by a municipal golf course. This roadside sign and a bronze plaque are the only tangible evidence the institution ever existed. Photo by Ruth Van Steenwyk of Aberdeen, South Dakota, taken September 3, 2018.

It represented an amazing turnaround, then, when in 1933 the Secretary of the Interior and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs sent out press releases with headlines like “Sane Indians in Asylum” and “Director Says Indians ‘Chained to Pipes.’” Between 1902 and 1933, the status quo had obviously exploded.

Attendants had mistreated patients in various ways for the entirety of the asylum’s life, and this could be addressed through reforms. But even the most determined advocates couldn’t change its environment. In 1909 Dr. Turner’s replacement, Dr. Hardin, discovered a woman confined to bed in such miserable filth that maggots were crawling around in her feces. This happened while Dr. Hummer was on vacation, and Dr. Hardin did his best during that absence to oust Hummer from his position. Hardin got employees to sign a petition requesting the Indian Bureau investigate the situation and later got a group of employees to swear out nineteen charges against Hummer. They included allegations that Hummer gave patients insufficient rations and overcrowded the dormitories. One allegation specifically charged Hummer with gross neglect in the case of the female patient with maggots.

An inspector did come out and discovered that many of the allegations were true. He told his superiors Dr. Hummer wasn’t the right man for the job and should be replaced. Then for the first time the Commissioner of Indian Affairs sent a medical inspector to look at the facility. That inspector also felt there was a significant problem at the institution due to Dr. Hummer’s mistakes and temperament. He didn’t outright suggest that Hummer resign, but he didn’t oppose it, either. He concurrently recommended the Indian Bureau point out Hummer’s mistakes and chastise him, and that was the suggestion the Bureau took up. The Commissioner sent Dr. Hummer a stiff letter, and that was the end of it. Dr. Hardin resigned and Dr. Hummer stayed in charge.

Many similar inspections and negative reports followed, but so did glowing reports from friendlier inspectors. One committee from the nearby town of Sioux Falls assured the Indian Bureau that even though language barriers prevented them from actually speaking to the patients, committee members were sure by their attitudes that they were fond of Dr. Hummer and his staff. Canton’s local newspaper always gave positive coverage. Hummer seemed invincible, and by 1933 he was entrenched in the local community and its affairs. With a Depression going strong the entire town would do all it could to keep the asylum open, and by that time, as the only medical director the asylum had ever had, Hummer was identified strongly with the asylum.

His patients were still helpless. Even though the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 gave Native peoples citizenship, individual states controlled their right to vote. Many imposed barriers (like literacy tests) to prevent it, and it wasn’t until the federal Voting Rights Act of 1965 that any significant protections were put in place. Patients and their families were still poor, uneducated, and without medical cultural authorities who could defend their behaviors to outsiders.

But certain critical mindsets had altered. In 1908 a highly educated Yale graduate, Clifford Beers, wrote a book about his experiences in an insane asylum, which began with his being held in a straitjacket for 15 hours when he first arrived and continued with his having to sleep in one for the next three weeks. Beers became a vocal and powerful advocate for mental health care reform. With the advent of the Progressive era, muckraker journalists used their platforms to attack monopolies, child labor, industrial corruption, the rampant adulteration of food and drugs, and the truly stomach-churning practices of the meatpacking industry. Reform was everywhere.

There was even reform for Native Americans. In 1908 an important ruling affirmed their water rights when they moved to reservations, and an examination of tuberculosis among the population found disturbingly high rates, triggering attention to other health issues. Funding for medical services increased enormously, from $40,000 in 1911 to $350,000 by 1918. Even the Commissioner of Indian Affairs was not immune to investigations, with Commissioner Robert Valentine finding himself on the receiving end of two separate examinations instigated by President Taft and the Justice Department, in 1912.

Attitudes toward Native culture were also changing. Reformer John Collier joined a friend at Taos Pueblo in New Mexico in 1921 after appropriations for one of his programs in California dried up. There, Collier was impressed with the Pueblos’ culture and appalled at their living conditions. That experience made him a vocal and effective advocate for Indian rights.

Other Progressives managed to raise their voices in support of Indian causes in various magazines, calling the government’s treatment of them shameless and legalized robbery. They were attacking not just a person who might have mismanaged a program, but the entire Indian Bureau. In 1926 the Secretary of the Interior ordered a far-reaching investigation of conditions on all reservations and at all boarding schools. Collier and other reformers used the information it uncovered to great advantage in later clashes with the Indian Bureau. And in 1929, an exasperated Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Charles Burke, ordered a thorough investigation into Canton Asylum. This time it wasn’t going to be conducted by anyone in the Bureau, friendly colleagues of Dr. Hummer, or even an agency in South Dakota. He asked for a staff psychiatrist from St. Elizabeths (the only other federal insane asylum) in Washington, DC.

The country’s-—and particularly the government’s—-changing attitude toward Native peoples became critically important for the asylum. When Franklin D. Roosevelt began his first term in 1933, he did so with new ideas, new people, and a New Deal. Progressives and long-time Indian advocates like Harold Ickes and John Collier were appointed Secretary of the Interior and Commissioner of Indian Affairs, respectively. In 1933 as he prepared for his job as Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Collier ran across the report from St. Elizabeths which had been gathering dust somewhere in the Indian Bureau. The inspector, Dr. Samuel Silk, had made some horrifying discoveries—-breakdowns in care which included a bedridden patient with a brain tumor padlocked in a room, a ten-year-old boy in a straitjacket padlocked in a room, and an epileptic girl chained to a hot water pipe, to name a few. Dr. Hummer, himself, had already admitted in an American Medical Association survey a couple of years earlier that he didn’t have staff meetings, gave no training to nurses or attendants, and provided none for staff performing any kind of therapy. Silk discovered that Dr. Hummer kept few records, and let attendants make stereotyped psychiatric progress notes. One elderly woman on a 12-hour shift was responsible for two floors in the main building and two wards in the hospital.

Though Collier and Ickes were outraged by the findings, they were thwarted in their efforts to act on them by people who wanted to protect Dr. Hummer and/or keep the asylum open. During legal proceedings Dr. Silk went back to the Canton Asylum and found basically the same conditions he had found the first time. He had come with the additional task to re-classify patients so they could take a train to St. Elizabeths, but one of Canton Asylum’s supporters managed to get an injunction against the move.

To overcome that obstacle the Department of the Interior began issuing national press releases which quoted details from some of Dr. Silk’s findings. Suddenly it became a lot harder to make a case for keeping Canton Asylum open and supporters drifted away.

The government filed (and won) a brief to dismiss the injunction against the removal of asylum patients, Collier fired Hummer, and in late December a train arrived in Canton to take sixty-five patients to St. Elizabeths. The Canton Asylum for Insane Indians had stood firm from December of 1902 until April of 1933, when Collier became Commissioner of Indian Affairs. Once he took over, the facility only survived another eight months.

Canton Asylum’s short history is complex and sad. This piece can by no means discuss all the factors that played into committing Native peoples there or the reasons for the dismal conditions that existed. However, one important factor that can’t be denied is the Indian identity of its patients. In an era that assumed Native peoples were barbaric and inferior, government authorities were sure to trample over both their rights and their dignity. Of the 90 patients he examined, Dr. Silk believed only 25 - 30 of them were actually insane.

Placard which is the only reminder of the indigenous people who died at the Canton Asylum and were buried on its grounds in unmarked graves. Photo by the staff of On Being.

He believed that a good number of patients were only mildly affected with mental problems and could live on their reservations with their families. He believed that others whom he thought were mentally deficient should go to a facility set up for that sort of patient. Silk also pointed out that Canton’s population was being judged “by the standards of the upper class of cultured white people.” He asked, “Is it fair to keep them at Canton because some minor difficulty landed them there?”

It was a good question. Silk found that many patients had originally come to the asylum because they had caused trouble on their reservations or had gotten drunk or assaulted someone. Dr. Hummer considered these patients mentally deficient because they couldn’t read or write, though Silk pointed out that they worked at tasks with little or no supervision once they were at the asylum. Unfortunately, Dr. Hummer liked to keep his patients once he got them and kept them at the asylum whether he considered them insane or developmentally handicapped.

Yet, how could he tell one way or the other? He couldn’t speak their languages and didn’t ask for interpreters. Patients couldn’t take any of the sorts of tests that might have pointed out their real issues. It seemed that Hummer couldn’t be bothered to educate himself about Native cultural mores, which might have brought these differences into consideration.

For instance, silence and lowered eyes were perfectly acceptable Native behaviors in any circumstances So were long silences and minimal body movements. Hummer interpreted these things as indicative of low IQ or a mental condition. It’s likely that many of Hummer’s patients came before him in either a belligerent or confused state, which he would have attributed to insanity. These examples highlight only a few of the problems the culture clash would have created, but it’s easy to see that fairness wasn’t front and center in the admission process.

In fairness it’s also necessary to say that that not every attendant was abusive or unfeeling, and considering the extreme poverty on many reservations, Canton Asylum may have been a better place for some patients to live. Some patients ended up at Canton Asylum because they had health problems their families and reservations couldn’t address while the Asylum could. Some patients truly did have psychological conditions or needed help their reservations couldn’t give them. For instance, for many years during this era, a medical condition like epilepsy was considered a form of insanity. No matter their race, people with epilepsy too often faced a lifetime in asylums until advances in medicine at last helped control their seizures.

Canton Asylum probably couldn’t have existed except in the era it did. Still, its history provides a lesson for any age about how easily the balance of power can be disrupted for any group of people and the consequences when that happens.