Driving through the idyllic landscapes of Grundy County, Iowa, past sprawling fields of corn and towering windmills, one might stumble upon a structure that seems oddly out of place. It’s not a barn, nor is it a traditional factory. This is a Bitcoin mining operation, a digital gold mine of the modern age, sitting unassumingly in the rural heartland of America.

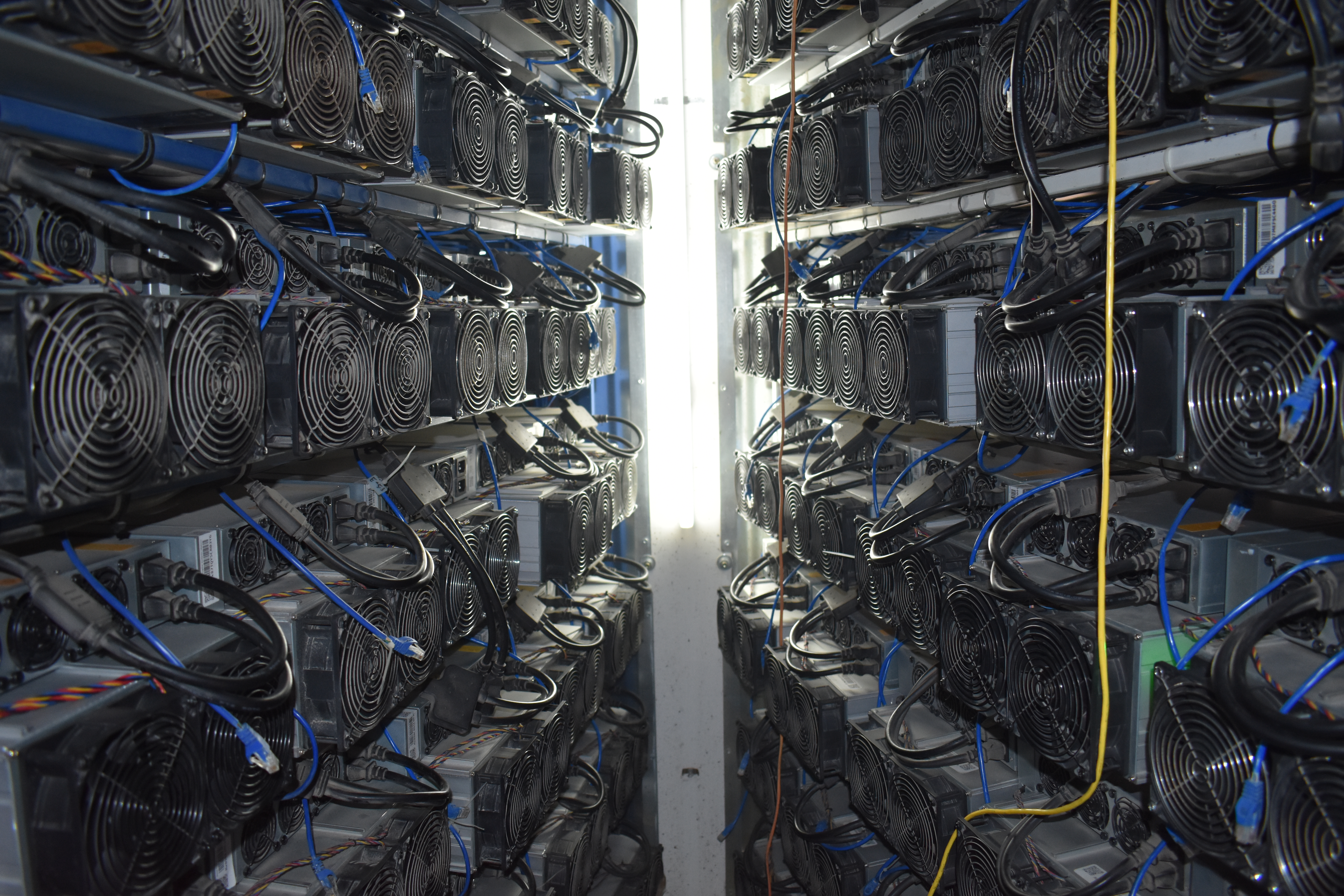

Here, near the town of Grundy Center, thousands of computers work tirelessly, crunching complex algorithms and calculations to mine Bitcoin, the most popular of the digital cryptocurrencies. Massive fans cool the machines, emitting a resounding roar that drowns out even the loudest farm equipment that passes on the nearby gravel roads.

Bitcoin, like other mineable cryptocurrencies such as Ethereum and Litecoin (neither of which is mined at the Grundy Center facility), operates on a decentralized network on which transactions are verified not by a single authority, but by multiple computers around the world. This requires immense computational power and, consequently, because these computations are performed by the miners’ banks of powerful networked computers, a substantial amount of electricity.

As the price of Bitcoin rises to all-time highs, so does the potential profit for miners, fueling a competitive rush to deploy more machines and use more power.

In rural communities like Grundy Center, the introduction of such operations presents unique challenges and opportunities. Local sentiments are mixed, some seeing it as an economic boon while others are wary of potential environmental repercussions.

For towns like Grundy Center, Iowa, Bitcoin mining poses unique challenges and presents unique opportunities.

“I know that people work at that Bitcoin thing, they come in here sometimes, but we don’t really understand it. It’s another type of currency, that’s all I know,” said Natalie Kracht, owner of Grundy Center organic coffee shop Natural Grind. “I think it’s great for them if they’re bringing in opportunities, but I also always worry about the type of emissions that could be dangerous.”

Jordan German is a consultant at MiningStore, which operates the Grundy Center facility as its flagship or “guinea pig,” as well as other facilities in Union and St. Anthony, Iowa. He explained the significance of the operation’s location in Iowa: “Iowa is a [the] second leading wind power generation state in the nation. It offers a mix of renewable energy sources, which is crucial for mitigating the environmental impact of our operations.”

Abundant renewable energy sources means Iowa produces more power than it consumes, holding electricity costs down. That spells lower costs for energy-hungry cryptocurrency mining operations.

That is true. The energy mix that powers the mining facility is provided by the Grundy County Rural Electric Cooperative, one of nine rural electric cooperatives and one municipal cooperative that collectively own Corn Belt Power Cooperative. According to the latest available figures, in 2021, the power which runs the MiningStore facility comes from a mix of approximately 42 percent coal, 20 percent from various renewable sources, 25 percent purchased power, and nearly 13 percent from other sources.

The energy demands of Bitcoin mining are immense. According to the MiningStore website, the operating capacity of the facility is currently six megawatts of energy. This translates to an annual usage of 52,560 megawatt-hours if it operates continuously at that rate. The company has plans to expand to 18 MW.

The energy demands of crypto miners like MiningStore are ‘immense.’

To put this in perspective, the average home in Iowa used about 11.2 megawatt-hours of electricity in 2022. Therefore, the mining site’s energy consumption exceeds the combined usage of all residential customers in Grundy Center, which has a population of 2,800.

“We had a Bitcoin ATM machine in here for a while and I don’t know if anyone used it or touched it, ever,” said Joel Johnson, store manager at Brothers Market in Grundy Center. “It’s scary,” he said when informed of the energy usage of the facility. “I’d like them to move as far away from here [as possible], I don’t want them around here.”

Additionally, the facility’s energy use is three times higher than the total annual energy consumption of Iowa’s Grinnell College, which caters to over 1,600 students, and is estimated to be around 2.16 MW.

Given the energy mix, the center would generate approximately 56,023 tons of CO2 per year, equivalent to the emissions from about 12,179 passenger vehicles in a year.

“As long as they’re paying as much as we all are and are not causing any problems, I am okay with them being here,” said Jill Krausman, owner of the Landmark Bistro in Grundy Center.

However, they actually pay less. Iowa produces more energy than it consumes and often exports it to neighboring states and cities like Chicago. By “using up” this excess energy generated closer to the source, MiningStore can access discounts from power providers who benefit more from having the energy consumed locally.

“They offer us a lower power rate than what you would even get like at home,” said German. “Because we’re using it up for you so they earn the money on that cost that would otherwise have been wasted for the power purchase. That’s the short and sweet energy arbitrage.”

That same affordable energy has also moved major companies like Google and Facebook to establish their own large data centers, operating thousands of computers, in Iowa.

The presence of such heavyweights is a boon for MiningStore in another arena as well: lobbying.

“We’re kind of piggybacking on some of the big boys there that got benefits,” said German. “The politicians and others put together tax incentives to attract them to Iowa.”

Such political leverage is important to MiningStore and other datamining operations like it. In Arkansas, for instance, legislation known as the “Right to Mine” act was passed to protect cryptocurrency facilities from local zoning laws, stirring controversy among residents disturbed by the incessant noise and night-time glare of these digital mines.

Similar concerns echo in Grundy Center, despite the Bitcoin mining operation being located eight miles west of the town. Local residents are torn over the actual advantages brought to their community.

In Grundy Center’s Landmark Bistro, customer Deb Cooley talked about her limited interactions with the facility: “Not a lot other than they rented a portable restroom from me. But what are they really giving back to the community?”

Hannah Aman, who works at the Grundy Mutual Insurance Association, was more optimistic. “I need to do more research, but I can definitely see the benefit of it; it creates new jobs,” she said.

That seems doubtful. Bitcoin mining is largely automated, requiring minimal staffing, which limits its potential for job creation but often increases its appeal as a source of passive income for investors and miners.

The industry is also expanding.

In 2021, Cedar Falls Utilities in Iowa agreed to host cryptocurrency mining operations by leasing space at their utility site to Simple Mining and Energy Conversation Group, as reported by the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier in June of 2022. A site in Kearney, Nebraska, uses about as much electricity as the 73,000 homes surrounding it, while another in Dalton, Georgia, consumes nearly as much power as the nearby 97,000 households. A mine in Rockdale, Texas, uses approximately the same amount of electricity as the closest 300,000 homes, making it the most power-intensive Bitcoin mining operation in America, according to a New York Times investigation.

In August of 2022, the Iowa Black Hawk County Board of Supervisors rejected a proposal to rezone land for a cryptocurrency farm, citing concerns over noise and energy consumption.

Similarly, Grundy County in 2022 turned down a proposal for a second MiningStore location . In January 2023, MiningStore approached Hardin County in north central Iowa, seeking to rezone two agricultural parcels to designation as a manufacturing zone, to facilitate the establishment of mining sites adjacent to Midland Power Cooperative’s electrical substations.

The company still plans to expand in Grundy Center, according to German. Already, additional structures , built with integrated fans, now house more computers outside the main white Quonset hut to create extra space. On a recent visit to the facility, stacks of newly shipped computers, still unboxed and branded with large letters spelling “CHINA”, were visible inside the hut.

MiningStore has plans to expand in Grundy Center, with facilities built to house more computers.

Before June 2021, China was the primary hub for Bitcoin mining. However, citing high energy consumption among other factors, China temporarily expelled many Bitcoin mining operations. This led to the United States rapidly ascending to global leadership in the industry.

In September 2022, the White House reported that global electricity consumption for cryptocurrency mining ranged from 120 billion to 240 billion kilowatt-hours annually. This amount surpasses the total yearly electricity usage of some nations, including Argentina and Australia. The increase in demand comes at a time when there is a global push to reduce electricity consumption to combat climate change.

By keeping operations in Iowa, where a larger portion of energy comes from renewable sources, the negative environmental consequences can be mitigated.

German points out that it’s practical to maximize cryptocurrency mining in Iowa due to the state’s significant proportion of renewable energy, whereas energy production in other locations is often less sustainable. “If we turn off, the bitcoin network doesn’t care. Something else is on, it could be located in Brazil, China, North Korea, anywhere,” he said, implying that energy production in these countries relies more heavily on non-renewable sources. By keeping operations in Iowa, where a larger portion of energy comes from renewable sources, the negative environmental consequences can be mitigated.

As the digital age encroaches upon the traditional landscapes of Iowa, the juxtaposition of cutting-edge technology and rolling countryside paints a complex picture of modern rural America.

In Grundy Center, the same winds that once turned the mills and watered the crops are now being harnessed to charge smartphones and power cryptocurrency computers performing trillions of calculations per second.

MiningStore’s ambitious expansion, coupled with the global surge in energy demands by similar cryptocurrency mining operations, presents a profound challenge to the use of resources in the prairie region.

What is Bitcoin?

The workings of Bitcoin can be inherently complicated, but here’s a simplified explanation. Bitcoin is a digital currency, known as cryptocurrency, because it uses cryptography to secure transactions. Cryptography is the process of writing or solving codes so that only the intended recipient can read a message. Bitcoin transactions are secure and not easily manipulated. Unlike traditional currencies issued by governments (like dollars or euros), Bitcoin operates on a decentralized network of computers spread across the globe. This network upholds and verifies transactions without the need for a central authority, such as a bank or government.

Bitcoin is often referred to as “digital gold” because, like gold, it is a scarce and valuable resource. There is a cap, set by Bitcoin’s protocol, on the total number of bitcoins that can ever exist — 21 million. This scarcity contributes to Bitcoin’s value — around $63,000 per “coin” at this writing — along with its security features and increasingly common acceptance as a means of payment for goods and services. The value of Bitcoin increases as more people use and invest in it, driven by demand and its limited supply. As of now, analysts expect Bitcoin will be “mined” for the next 100 years or so.

How does Bitcoin mining work?

Bitcoin mining is the process through which new bitcoins are introduced into circulation and transactions are verified and added to a public ledger, known as the blockchain. Here’s a breakdown of the mining process:

- Transaction verification: Miners gather transactions from a pool and check their validity. They ensure that the digital signatures are authentic and that the transaction details align with the blockchain’s history. This involves checking that the sender has sufficient balance and that the transaction has not been previously spent.

- Solving the puzzle: To add a “block” to the blockchain, miners must solve a complex computational math problem, also known as a “proof of work.” This process requires an enormous amount of computer processing power and energy. The puzzle involves finding a number that, when combined with the block’s data and run through a special mathematical function called a hash function, produces a specific result. This process is essentially a race among miners, as only the first one to solve the puzzle gets to add the block.

- Adding to the blockchain: The first miner who solves the puzzle gets to add the new block of transactions to the blockchain. As a reward, they receive newly minted bitcoins and transaction fees. The amount of these fees can vary but typically ranges from a few cents to several dollars per transaction, depending on network congestion and transaction size.